Peter Friedrich Wilhelm Klopp (1852 – 1900)

The little Peter Friedrich Wilhelm Klopp was born in Magdeburg on January 1, 1852. On his father’s death, he was just nine years old. As the eldest son, he experienced how his mother with her children after the loss of the provider plunged into even more dismal misery. The circumstances under which Peter Friedrich Klopp found his way into the milling business may have to do with the former family connection of his mother, who originally came from that area.

The Magdeburg period of the Klopp family line stood under no good star. In spite of hopeful beginnings their economic situation remained at a relatively low level. The family of the former Prussian recruit and later ´transport enterpriser´ Heinrich Friedrich Klopp experienced noticeably the petty-bourgeois and proletarian living conditions in the city of Magdeburg of the 19th century.

Already before 1860, the most bitter poverty of all the chronicled events hit our Klopp family line very hard. The early death of the father only 40 years old and the passing of his mother at the age of 44 reveal that for the change over from peasantry to the commercial and industrial milieu a heavy tribute had to be paid. Health and vitality were going to be sacrificed.

At the death of his mother in 1870, Peter Friedrich Klopp was only 18 years old. Perhaps out of concern for her eldest son’s health with the help of family connections she may have sent him into the country to Jersleben near Wolmirstedt. There, opportunities in the miller’s apprenticeship program in at least three mills were waiting to be taken by the young enterprising man: Herrenmühle, Mittelmühle and Vordermühle.

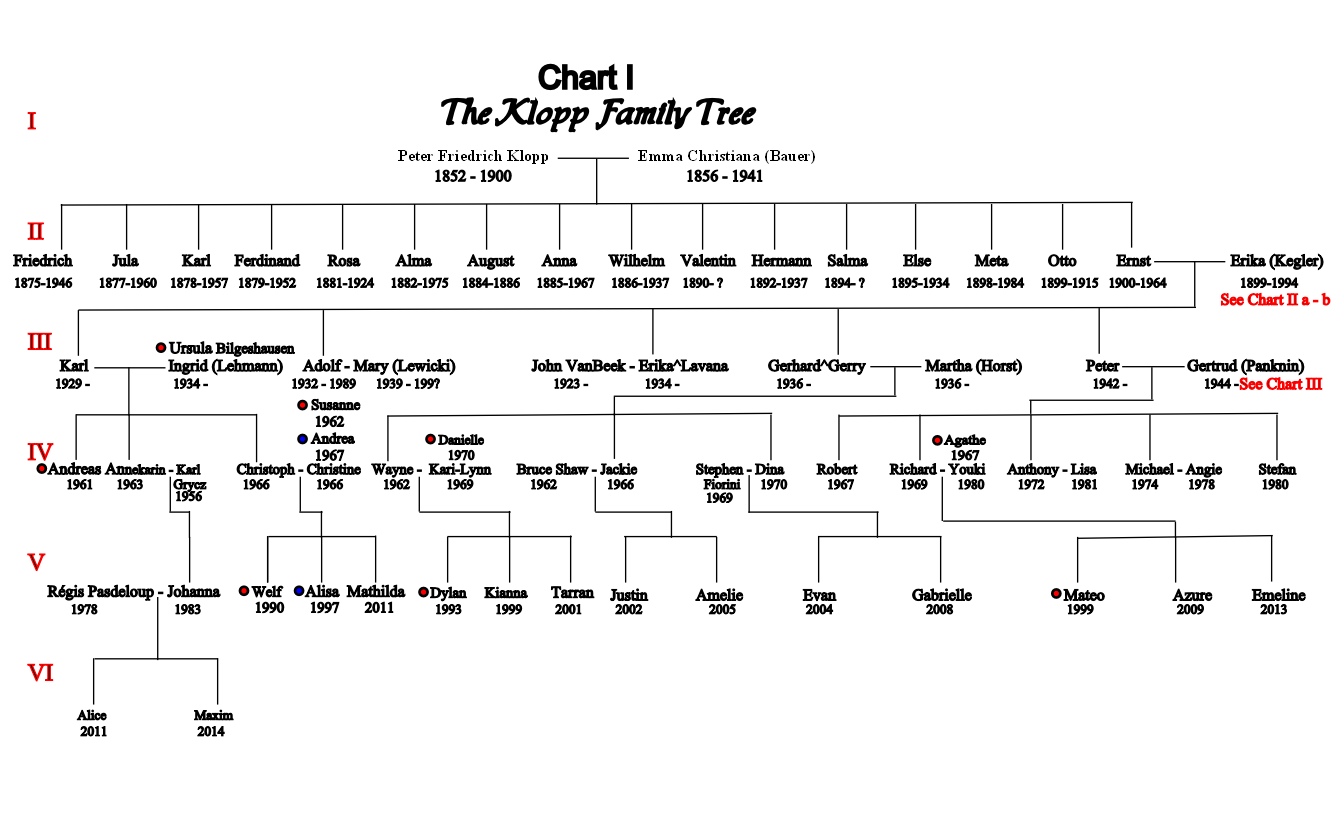

Miller’s apprentice Peter Friedrich Wilhelm Klopp and Emma Christiane (née Bauer) were married on September 27, 1874, in the village church at Jersleben. He was 22 and she was 18 years old. Their marriage of over 25 years was blessed by a phenomenal fecundity, coming close to the Austrian Empress Maria-Theresia. Sixteen children emerged from this union.

A few years after the wedding P. F. Klopp became qualified as a master miller. Several attempts of running his own mill (e.g. the ‘Düppler Mill’ at the southeast end of Olvenstedt) as well as working in three different other mills in Jersleben failed. Around 1890 already blessed with seven children it appeared that he was finally able to secure a solid economical foundation. Together with his eldest son Friedrich (grandfather of author Eberhard Klopp), who had just finished his rope making apprenticeship, he acquired a house in Wolmirstedt. Peter concentrated on the production and sale of flour, while Friedrich operated the rope making plant. Housing for a very large family, storage facilities for grain, flour and feed, manufacturing shop etc., were all under the same roof.

Rivalries, quarrels, and petty disputes about who was in charge of it all did not create a climate conducive to a prosperous enterprise in the Magdeburger Straße (now Friedensstr.). When brother Ferdinand, also a trained rope maker joined them, Peter began to worry about losing his independence and looked for a way of dissociating himself from the troublesome business in Wolmirstedt.

Supported, perhaps even driven by his energetic wife, Peter F. Klopp returned with his family to Jersleben, where he established his own business of producing and selling flour. He seized on a golden opportunity of acquiring a long-sought-after watermill. All indications are that he was not to see his final dream come to fruition. For documents show that widow Emma Klopp was the owner of the mill in 1901 one year after her husband’s death.

Peter Friedrich Klopp was good-looking, handsome, slightly obese, but a giant of a man. He was generally of a cheerful disposition and was not disinclined to a good occasional drink in the genial like-minded company every once in a while. In the middle of May not long before my father’s birth, he was riding home from a hunting party. It appears that he often left direction and speed to the discretion of his well-trained horse. Maybe on this chilly night, he had had just one drink too many. Falling asleep on horseback is never a good idea, especially when you are in that cozy state of inebriation. Inevitably, he slipped off the saddle, and the horse trod home without him. Early next morning travellers found him lying half-conscious on the roadside. He was sober by now but suffered from a severe case of hypothermia. Soon after, he acquired a kidney infection, from which he was unable to recover. He died on the 26th of June 1900 at the age of 48.

Emma Christiane Klopp (1856 – 1941)

The miller’s apprentice Peter Friedrich Klopp became acquainted with Emma Bauer, the daughter of the factory inspector Friedrich Wilhelm Bauer, born in Groß Ottersleben on March 3, 1818. Her father had moved to Jersleben, where he died on April 4, 1886. Emma at the time of his death was only 12 years old and was the fifth child out of her father’s marriage with Rebecca Sophie, who died in Wolmirstedt in 1898.

What brought Emma’s family originally from the Würzburg area to Jersleben, author Eberhard Klopp explains in his ‘Letter to the Descendants’ as follows:

Already blessed with four children Emma’s parents lived from at least 1855, most likely even sooner, in Rottendorf near Würzburg. In this village, the wealthy Jewish Würzburg banker Joel Jakob von Hirsch managed an increasingly flourishing sugar factory. The socially conscious entrepreneur and owner of a large estate ‘wanted to provide a livelihood for lower-class people, for he was kindhearted toward the poor people.’ Von Hirsch’s declared intention was to make the South German market independent of ‘the dominant North German sugar factories.’ To this end, he hired specialists from Magdeburg, Cologne, Baden and Holland. An additional incentive was the voluntary health insurance fund established by the factory owner for the workers and their family members of his Rottendorf plant. This, at that time, was a rare, but socially groundbreaking undertaking.

Attracted by such favourable and promising working conditions, the Bauer family settled in Franconia probably until the shutting down of the Rottendorf plant. There in the House No. 3 (Dürrhof}, the property of the aforementioned banker, Emma Bauer was born on January 27, 1856.

Unfortunately, due to a shortage of water, it was no longer possible to process sugar beets. The production was shut down, which was a major cause for the Bauer family to relocate to the sugar beet region in the north near Magdeburg.

Miller’s apprentice Peter Friedrich Wilhelm Klopp and Emma Christiane (née Bauer) were married on September 27, 1874, in the village church at Jersleben. He was 22 and she was 18 years old. Their marriage of over 25 years was blessed by a phenomenal fecundity, coming close to the Austrian Empress Maria-Theresia. Sixteen children emerged from this union.

Emma, pregnant with her last son, was on her own with at least six underaged children. The youngest, Friedrich Ernst Klopp (my father) was born four weeks after his father’s death on June 28, 1900, in Wolmirstedt.

She could not depend on the two eldest sons. Friedrich born in 1875 had just started his own family. Karl born in 1878 was a Bavarian soldier in China. The only possible support came from Ferdinand born in 1879. Forced by necessity, but with a considerable amount of pluck and enterprising spirit, she confidently embarked on her long-cherished plan to acquire a milling business. She figured that this move would also be of benefit to her younger children. The last owner of the mill Wehrmühle had died without an heir. Emma seized the opportunity.

One year after her husband’s death, she acquired the property on May 22, 1901. Its total size including the house, yard, garden, fields and meadows was 4650 m². The purchasing price was a little under 13,000 marks. Widow Emma Klopp must have considerably enlarged the property by way of additional purchases. For in 1903, she sold it almost double in size to her brother Karl Bauer for 13,000 marks. He was running the mill also for about two years. It is noteworthy that the 20-year-old eldest son born in 1875 did not take part in any of the dealings related to his mother’s property. Also, Ferdinand born in 1879 seems not to have been involved. At any rate, with the abandonment of the mill, the entire project of late father Peter Friedrich Klopp, – the project under the fanciful name ‘the flour shop and mill operation’ had definitely failed.

In 1903, the house in Wolmirstedt had become too crowded for the 47-year-old widow. The mill ‘Wehrmühle’, like the previous mill enterprises in Osterweddingen or Olvenstedt, had turned out to be unprofitable and had been sold. At that time eight older children had already left the nest, two had died, but Emma, all on her own now, had to feed her family of six underaged children: Hermann (11), Selma (9), Elsbeth (8), Meta (5), Otto (4) and Ernst (3).

In the spring of 1904, the fatherless family without a male protector moved to the distant region of West Prussia and beyond the Weichsel River plunged into a risky farming venture.

Since 1886, the Prussian Royal Settlers Commission had been attracting interested people from the Reich to settle in the former Polish territory of Pomerelia. On the basis of a rental or temporary lease agreement, German settlers could acquire estates or parcels of land, which had been transferred from the former Polish owners for appropriate compensation to the Prussian state.

So-called ‘estate agents’ where the brokers, who published their land offers in newspaper ads and in personally addressed letters. They were often Jewish grain merchants, who through their extensive travels were familiar with the local situations in West Prussia and advertised them accordingly.

As far as the history of the Klopp family is concerned, it is likely that Emma had gone on an exploratory journey to the county of Briesen and had at this occasion met the real estate agent ‘Grasmück’. When daughter Anna gave birth to her son Georg in 1904 at Mother Emma’s new place in Elsenau, the legend of an illegitimate father, the Polish Jewish Grasmück, appeared very plausible to the gossipy and fanciful family members in Wolmirstedt.

After the sale of the mill for 13,000 marks, Emma Klopp, my grandmother, had about 20,000 marks at her disposal. The average purchase price for estate and farmland in and around Elsenau in the county of Briesen, West Prussia, was about 1400 marks per ha. The fields were often swampy and needed to be drained to be of any profitable use. The estate comprised an area of about 245 ha according to old Prussian surveying records. It is obvious that Emma could not have acquired in 1904 this property with a paltry sum of 20,000 marks. Consequently, she had not have become an estate owner, but rather a leaseholder of a small farm settlement. Correspondingly modest were the looks of these settlements established at the end of the 19th century: tiny one-story brick houses with sheds for poultry, barns and small kitchen gardens on an area of not more than 25 m by 35 m.

Since 1908 Emma Klopp together with the help of her remaining children had been farming on the settlement at Elsenau for 10 years. The working conditions were not exactly rosy, partly because her hired personnel was unreliable, partly because the general market for agricultural products was often unprofitable. Her son Ferdinand moved in the same year to the Posen (today Polish Poznan) region to take over a dairy business.

Also from Elsenau her sons Hermann (1892 – 1937), Otto (1898 – 1915) and my father Ernst (1900 – 1964) moved out to pursue their own vocational careers and eventually joined the army. Here Emma received the news that Otto had been killed in Russia at the age of barely 18.

The effects of the Treaty of Versailles dictated by the victors of World War I brought about an economic collapse of Germany, which also lost large pieces of territory in most cases without a plebiscite. The loss of West Prussia meant that East Prussia had no rail or road connection with the rest of Germany.

Emma took a quick and decisive action before the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles were implemented and managed to sell her property and in Elsenau, West Prussia at favourable market value. A few months later Polish would-be buyers would have been able to acquire the former German estates for a much lower price. In this chaotic time, Emma was able to profit from a combination of good luck and skillful maneuvering.

The decision to sell must have been made in January 1919 at the latest, when in West Prussia the first news reports about attempts of insurrection against the German state were circulating. Emma was spared the evil side effects associated with the forced separation of West Prussia from the German Reich. The spread of a pogrom-inspired atmosphere among the Polish people against Germans and Jews in the summer of 1920 escalated into looting, horrific abuse and arbitrary killings by Polish soldiers.

How much money Emma Klopp had made through the timely sale of the Elsenau property and how she invested it afterwards in a gainful and inflation-proof fashion, will remain a mere supposition. An unproven estimate of the figure may have been around 40,000 to 50,000 gold marks. At any rate, Emma and her family members did not emerge poor from the consequences of World War I.

In the late spring or early summer of 1919, Emma found an interim residence at her daughter Rosa and her husband August Diesing at the farmhouse In Lebus near Frankfurt, Oder. A longer stay at the Inn “Zum Stern” in Gommern near Magdeburg indicates that from this point on Emma Klopp had become financially independent.

From 1922 to 1927 and beyond, Emma’s years were filled with sustained travel experiences. Through personal involvement and many visits, she accompanied her children on their lives’ journeys. With the eldest son Friedrich Klopp (1875 – 1946), who in 1924 had become a widower in Hemsted near Gardelegen, she was no longer in contact. Similarly, with her third son Karl Klopp (1875 – 1957), who at that time was running a dairy business in Passau, she also seemed to have lost contact.

On good advice and financial help could count all those children, who during the rather tough times in Elsenau had supported her: foremost son Ferdinand with the takeover of the inn “Brauner Hirsch (Brown Elk), daughter Anna von Waldenfels with the acquisition of the estate near Passau, possibly also Wilhelm, the refugee from new Poland. Otto Klopp was killed in the war on the Eastern front. But the family nestling Meta had still to be looked after and cared for. Her youngest son Ernst Klopp (1900 – 1964), Peter’s father, was aiming to settle on a farmstead in Latvia. The other children had already searched and found their own ways.

For the time being, Emma joined her son Ferdinand’s family and lived from 1922 to 1923 in his inn ‘Gasthaus Brauner Hirsch’ (Brown Elk) in Elbeu.. Also, his brother Wilhelm had acquired a property on the same street. At the same time, she also visited the Diesing family in Schönebeck near Magdeburg, where her daughter Rosa’s husband was running a construction business.

After 1927, Emma by now 71 years old moved to the estate Panwitz, the property of Anna and Ludwig von Waldenfels, whence she devoted her time to her travelling passion for the rest of her senior years. Visits to her son Hermann in Breitenburg, Pomerania, to her son Ernst (Peter’s father) in Belgard, Pomerania and to her daughter Anna Scholz in Berlin have been reported. At the weddings and births of her grandchildren, ‘Öhmchen Emma’ was often present at these important events or appeared a short time after to offer her congratulations. In Alt-Valm, Pomerania, she most likely attended the funeral of her daughter, Else Stier, in 1934.

In October 1935 she spent some time in Berlin to be part of the wedding ceremonies of her youngest daughter Meta and experienced the festivities in the St. Hedwig’s Cathedral and the lavish banquet in the ‘Hotel Adlon’. At the castle Lagowitz, adjacent to the estate Panwitz, the wedding of her grandson Georg von Waldenfels (1904 – 1981) with his second wife Ilse Jannink took place at which Emma Klopp was present.

Emma Klopp (née Bauer), the caring and kind and central family figure for most of the Klopp clan, passed away after 14 peaceful years on May 23, 1941, at the Panwitz estate in the safe haven of her family. The little woman bent by old age did not survive a severe case of pneumonia after she had fallen down the staircase from her tower apartment. Her granite covered monument on the forest floor was in the shape of a semicircle of approximately 8 m in diameter. One can still find her graveside today about 40 m southwest of the Panwitz estate building amidst high trees in the park.