Crammed, Deloused and Harrassed

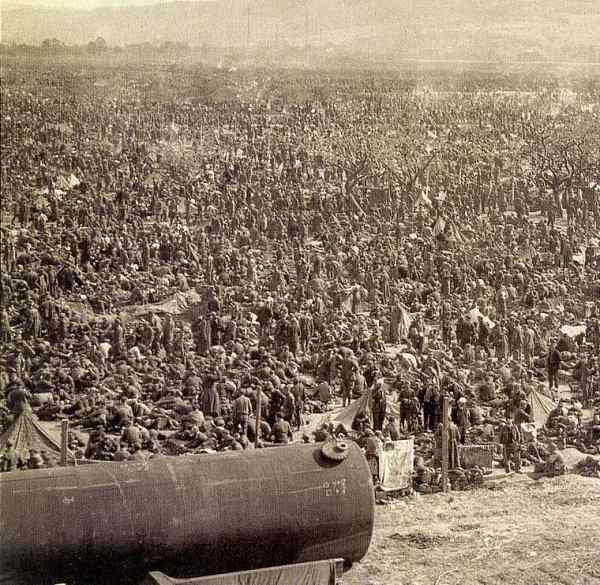

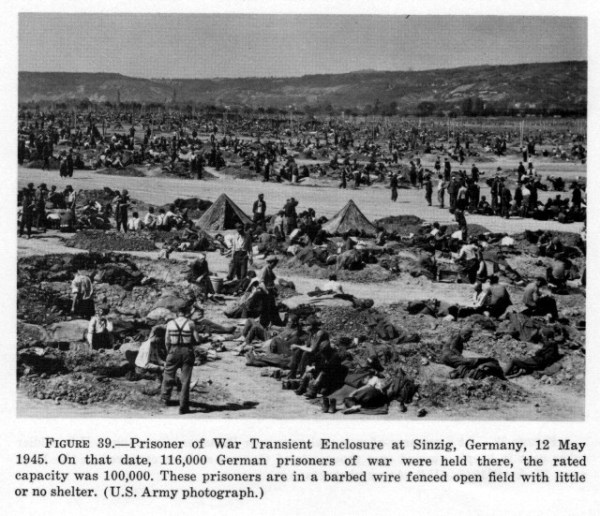

Then suddenly and just as unexpectedly as a balmy spring breeze and sunshine had brought relief, good food and drink cheered up the POWs. Bread, corned beef, cheese and calorie-rich soup, although not too plentiful, have now become part of their daily diet, supplemented by a few chunks of chocolate for dessert. Although the adage says that hunger is the best cook, they all agreed that the cooks were doing an excellent job. To round things off, they had as a beverage a choice of tea or coffee. The coffee tasted so good that many imbibed too much of the excellent brew, which kept them awake half through the night. On June 16, all men, whose hometown had become part of the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany, were put on a special list. Rumours about early release from their prison camp instantly circulated among Papa’s comrades. How soon would the Americans let them go home? Would army trucks drive them to the border? How would the Red Army men receive and treat them? Would Papa be free after his release from the camp? These were some of the questions and worries the POWs had. The troublesome thoughts burdened Papa’s heart at the time when he should have been rejoicing to be finally free from hunger and cold.

Near the end of the month, it rained again. But the air was mild, and the POWs now found shelter in the hastily erected wooden barracks. But they had to put up with cramped conditions. Space was so limited that there was not enough room on the primitive floor for everyone to sleep on his back. Packed tight like in a can of sardines, many had to sleep on their side. Thus, it was very likely that lice would have a heyday and spread like wildfire among the hapless bunch of humanity. The camp authorities had them march to the delousing stations to prevent the infestation from gaining the upper hand. There they had to undress and wait in the pouring rain for their turn to be deloused. Papa did not fail to see the irony, at least for this embarrassing moment. Like slaves powerless and naked, they stood before their black masters, who searched in a bout of chicanery for anything they deemed dangerous. Nail clippers and files, even pencils, were considered dangerous weapons and promptly confiscated. Papa must have hidden his precious writing tools in the sleeping quarters, knowing full well that he would be punished for having them in his possession. After being thoroughly deloused, they returned to their barracks and felt a lot better after receiving a bowl of sweet soup. Papa bitterly remarked that the worst form of chicanery did not come from their American guards but rather from their own ranks. Those lucky enough to be chosen as helpers and supervisors in the camp kitchen now turned against their comrades to be sure in part to impress their American guards. At 4:30 in the morning, when everyone was still fast asleep, they would holler with a commanding voice, ‘Get up, you sleepy heads! Pick up your grub!’ Everybody understood this message too well. For if you did not comply or you were too slow to respond, you would miss out on your breakfast and have nothing to eat till noon. From all the shelters, you could see the prisoners rushing to the source of food. To have something in your belly was more important than an extra hour of sleep. But when they arrived in joyful expectation of a nutritious breakfast, the German kitchen helpers were laughing their heads off at their successful prank and shouted, ‘Get back to sleep. You should know that we don’t serve breakfast until six!’