Karl and Adolf’s Perilous Journey March 1945

Karl’s Report – Part 4

We soon found out that the Russians were pushing hard directly to the coastline. Shots were coming out of the dunes aimed at the passers-by. German soldiers went into position and repulsed the attack, which would possibly have cut us off. Here is one impressive detail: A soldier was getting ready on the dune in the direction of the pine forest. An overly daring Russian fighter was hit and fell down and remained hanging in the lower branches. He wanted to get an overview of the scenario from the treetop.

I do not know why someone would throw bicycles into the sea. Anyway we got two of them out of the water, loaded our light luggage and moved ahead this way a lot faster. Near the water’s edge the sand was firm; only over the tidal inlets we had to lift our vehicles. The bikes were available to us for many more kilometres, until we caught in Neubrandenburg a train to Erfurt.

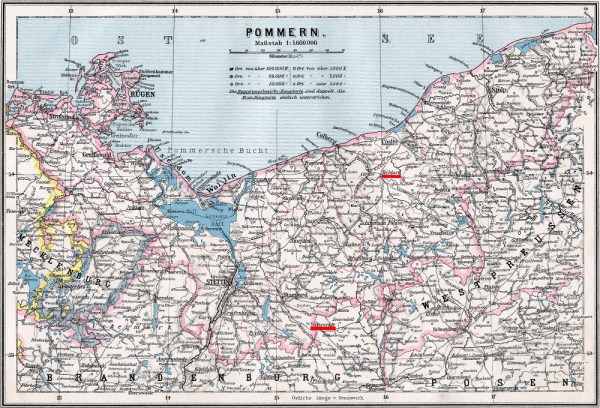

From the place, where we found the bikes, we soon reached the village of Dievenow located on either side of the arm of the Oder River, from which it got its name. On the east bank we had a major delay, because there was no bridge, but a ferry instead, which connected the ends of the old highway of the Reich I65 and which was no longer operational. The army had set up a pontoon service, which, when we arrived, was exclusively available for the troops. They consoled us civilians with the evening hours. We looked at the village. There were beautiful villas located near the beach like in so many resorts at the coast. We went into abandoned houses in search for food. The provisions we had with us had been exhausted. Where we had stayed overnight we had begged for food or often filled our stomachs at the military field kitchens. It was awkward that we had neither a tin bowl nor a spoon with us. Once we ate out of a steel helmet, the inner lining of which we had removed. In the houses of Dievenow we found very little, at most canned fruit.

In this beautiful place I should have received my paramilitary training. They were sending the male Hitler-Youth to so-called training camps, from which they were directly transferred to the troops. During our journey I always had the draft notice readily available in my pocket, but had no intention to look around and locate the camp to report for military duty.

Finally they let us two bicyclists onto a pontoon, some of which were ferrying constantly back and forth.. Now one could already hear heavy artillery fire close by. Shells hitting the water indicated that the Soviets intentionally were going to disrupt the withdrawal movements.

Much relieved we pedalled onward in a westerly direction, needed no longer to divert our march into forests and fields, but rode on decent roads. There were also organized centres of provisions through field kitchens. Also the military operations were less noticeable in the rural areas. The city of Wollin, a day’s march from Swinemünde, was only captured on May 4, 1945. We reached Swinemünde, the next city from Dievenow, already on March 12th, a date of horror in my memory.

We soon arrived at the small beach resort town of Misdroy, twelve km before Swinemünde on the main road to Stettin. We had more often heard the thunder of big guns from the direction of the Baltic Sea. The German navy, which not only carried the masses of refugees primarily from the East Prussia to safety, but was also actively engaged with its long range guns in support of the battle on land, and was shooting no-go areas against the enemy to safeguard endangered front lines. What we heard on March 12th, let the ground at a wide range shake and doors bang open and shut. The Americans and British had fooled the antiaircraft authorities by not flying in a straight line to the town of Swinemünde, but then for one hour intensively bombarded the relatively small town area. The bombing raid resulted in 23,000 dead. They rest on the German side on the Golm, a cemetery of an area of one square km. Swinemünde is Polish today.