Bericht über Wolmirstedt und die Klopp’s

von Dieter Barge – Chart II a – IV

Also Chart I – I & II

Als ich in Peter’s Bericht über die Klopp’s das Bild der Seilerei Friedrich Klopp in Wolmirstedt gesehen habe, interessierte mich sehr, wo das wohl war.

Edda und ich lebten doch selbst von 1980 bis 1990 dort.

Ich hatte ein Buch von Otto Zeitke und habe mir noch 2 weitere Bücher antiquarisch besorgt, diese hat Otto Zeitke gemeinsam mit Erhard Jahn geschrieben. Die Beiden haben sich als Heimatforscher sehr verdient gemacht, Otto Zeitke ist 1924 geboren und versteht es gut, die Berichte der älteren Leute interessant wiederzugeben. Erhard Jahn ist um einiges jünger und hat in Wolmirstedt ein Ingenieurbüro für Architektur.

Im ersten Buch “Das alte Wolmirstedt” fand ich dann vermeintlich die Seilerei Klopp !

Um sicherzugehen, habe ich bei Erhard Jahn angerufen, habe ihn nach Klopp’s gefragt und da kam sofort die Frage zur Seilerei Klopp zurück. Ich habe ihm einiges erzählt und ihn gebeten, mal das Bild in einer Mail zu betrachten und meine Vermutung zu bestätigen.

Das hat er auch getan und mir bestätigt, daß das Gebäude links neben der Druckerei Grenzau die alte Seilerei Klopp ist. Beide Gebäude befinden sich in der Friedensstraße, das ist der neue Name für den nördlichen Teil der ehemaligen Magdeburger Straße Er kannte auch das Bild von der Seilerei schon. Daneben ein aktuelles Bild von Herrn Jahn mit dem ehemaligen Seilereigebäude in der Mitte.

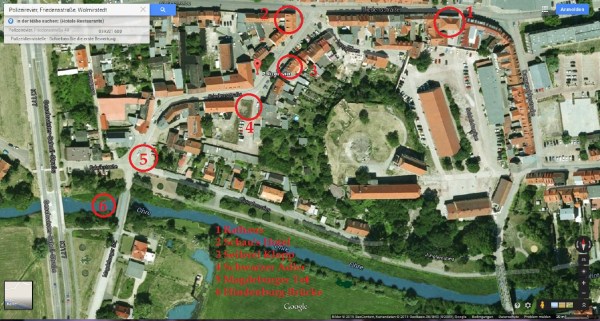

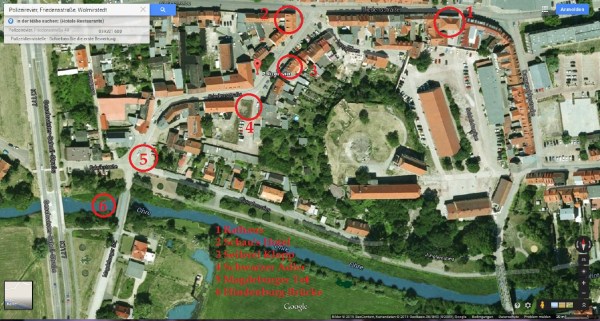

Ich stelle hier ein Google-Earth-Bild mit der Friedensstraße ein:

Herr Jahn hat mir auch erlaubt, Bilder aus den Büchern im Blog zu benutzen und erzählte, dass Anfang der 90-er Jahre ein etwa 60-jähriger Klopp bei ihm in Wolmirstedt war, nach Durchsicht seiner Aufzeichnungen fand er heraus, dass dies Eberhard Klopp war, also der Klopp, der das Buch:

“Ein Brief an die Nachfahren der Familie Klopp aus Altendorf/Brome und Wolmirstedt”

Teil 1 400 Lebensläufe zwischen 1590 und 1990

1997 Verlag Trier

geschrieben hat. Herr Jahn stand mit Eberhard Klopp an der Hindenburg- bzw. Magdeburger Brücke und dieser hat mit der Hand auf die Stelle gezeigt, wo von 1900-1912 die “Seilerbahn” der Klopp’s war. Inzwischen weiß ich, daß Eberhard der Großcousin von Peter Klopp ist.

Aus den 3 Büchern habe ich einen kleinen Abriß zur Geschichte von Wolmirstedt gemacht:

——————————————————————————————–

Das kleine Städtchen Wolmirstedt, 14 km nördlich von Magdeburg gelegen, wurde erstmals 1009 urkundlich erwähnt.

Wahrscheinlich während der Völkerwanderung bildete sich eine geschlossene Siedlung, die “Walmerstidi” genannt wurde, diese befand sich am Zusammenfluss von Ohre und Elbe und bildete unter “Karl dem Großen” einen östlichen Grenzort des großen Frankenreiches.

Am Ende des 13.Jahrhunderts änderte die Elbe ihren Lauf in Richtung Osten, heute mündet die Ohre bei Rogätz in die Elbe.

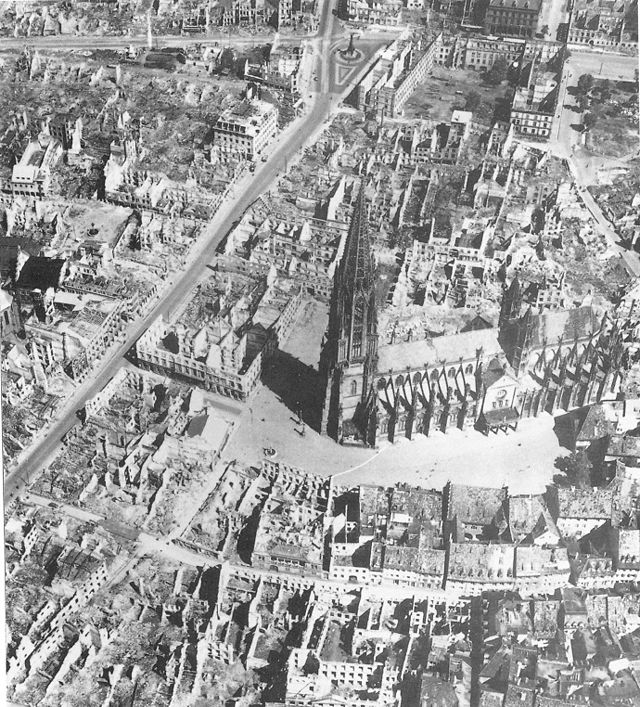

Im 30-jährigen Krieg wurde Wolmirstedt 1642 völlig zerstört, 1642 fand eine öffentliche Hexenverbrennung statt!

Einen Aufschwung gab es für den Ort nach der Besetzung 1807 durch die Truppen von Napoleon. Die Leibeigenschaft wurde abgeschafft, es gab mehr Freiheiten für Handel und Gewerbe und weniger Privilegien für den Adel!

1890 hatte Wolmirstedt 3868 Einwohner, nicht mitgezählt wurden die 50 Beschäftigten auf dem Junkerhof.

Die Magdeburger Straße, dort wo sich die Seilerei Friedrich Klopp befand, wurde 1365 noch als “Steinweg” benannt, sie war eine wichtige Durchgangsstraße von Magdeburg nach Norden. Die Passage über die Magdeburger Brücke der Ohre muss “sehr riskant” gewesen sein. Ein Fuhrwerk benötigte damals einen ganzen Tag, um nach Magdeburg und zurückzukommen.

1667 wurde die Torakzise (Wegezoll) eingeführt, das “Magdeburger Tor” wurde errichtet, 1812 wurde die Torakzise abgeschafft.

In der Straße siedelten sich Kaufleute, Handwerker, Fabrikanten, Handwerksmeister, ein Apotheker, ein Schmied und ein Kantor an. Die Straße war “420 Schritte” lang und endete am alten Rathaus, einem Renaissance-Bau.

1925 lebten 170 Familien in der Straße.

Die “Magdeburger Brücke” hieß zeitweise “Hindenburgbrücke”.

Markante Gebäude waren das Polizeiamt, die Buchdruckerei Grenzau, die den “Allgemeinen Anzeiger” herausgab (daneben die Seilerei Klopp), “Schau’s Hotel”, die Gaststätte “Schwarzer Adler” (1971 abgerissen), die Alte Schmiede, das Fachwerkhaus des Schlossermeisters Jänicke, die “Wildemanns Gaststätte und Pension”.

Einer von Wolmirstedt’s Originalen war der Wirt des “Schwarzen Adler’s, Kurt Güssefeld.

————————————————————————————————

Der heute über 90 Jahre alte Otto Zeitke ist ein toller Erzähler vom alten Wolmirstedt und seinen Bewohnern, da gibt es viele interessante Dinge zu lesen:

-Er berichtet, dass der Wirt einmal plötzlich sagte “Das kann’s doch nicht geben, wie der Schinder die Braunen hetzt”, dann lief er zum Fenster, sah auf die Straße, , schüttelte den Kopf und brummte unverständliche Flüche gegen den

Kutscher”.

-Auf dem Hof des Rathauses gab es den Karzer, das Gefängnis. Die Frau vom Polizisten Meier betreute und versorgte die Knastbrüder, der Volksmund sagte zu den Insassen, sie sind im “Cafe Meier”.

Ich habe mit Otto Zeitke lange nett telefoniert, er wirkt noch sehr jugendlich und berichtete mir, dass er die Kanuten in Wolmirstedt organisierte, er ist auch der Meinung, dass die Seilerbahn der Klopp’s am Ufer der Ohre gelegen haben muss.

Am 11.3.2015 war ich mit Edda in Wolmirstedt, wir haben die Friedensstraße von der Ohrebrücke bis zum alten Rathaus abgewandert und Fotos gemacht.

Ich stelle nun einige der Bilder neben den alten Aufnahmen aus den genannten Büchern ein. Den Anfang macht das Bild von Eberhard Klopp, das mir Herr Jahn freundlicherweise auch geschickt hat. Ich habe rot eingezeichnet, wo sich vermutlich die Seilbahn Klopp befand.

Vom ehemaligen Magdeburger Tor ging es dann aufwärts nach Wolmirstedt hinein.

Der nächste Abschnitt beginnt mit der Ecke “Schwarzen Adler”, führt am Haus der Seilerei Klopp und dem Polizeigebäude vorbei bis zum ehemaligen “Schau’s Hotel”.

Nun geht es im nördlichen Teil der Straße bis zum alten Rathaus.

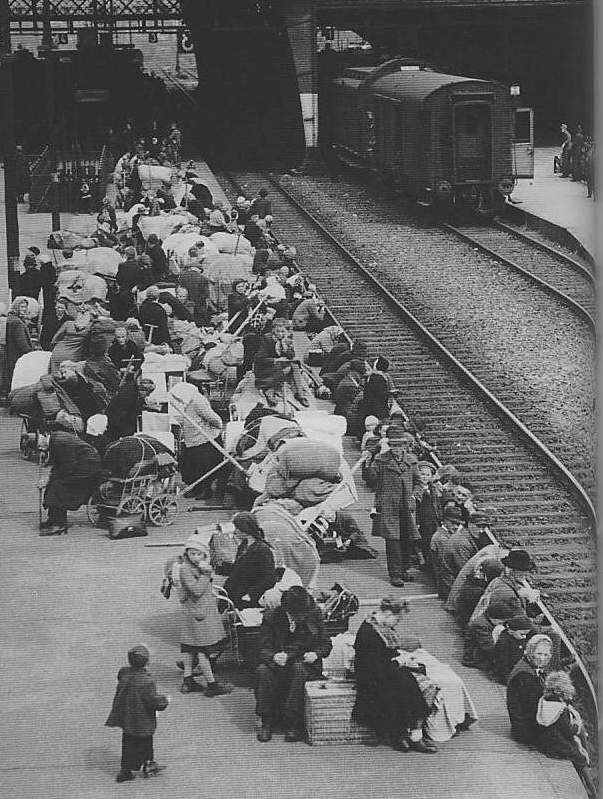

Zum Schluß noch 4 sehr schöne alte Fotos aus dem alten Wolmirstedt.