STEEP AND CROOKED: THE MINING RAILROADS OF THE CANADIAN BORDER

By Bill Laux

CHAPTER THREE

THE TRAIL CREEK TRAMWAY

1895 – 1896

Rossland was a rough, muddy, woman-less, mining camp of just 75 miners when the year 1895 opened. Then, in January, all over Red mountain the digging began to pay off. First, the War Eagle, under the Clark brothers, struck the main vein. The ore was rich and the mine began to pay monthly dividends starting February First. Soon after, the Centre Star found high grade ore, and it too became a paying mine. Following closely, came bonanza strikes in the Black Bear, the Josie, the Nickel Plate, the Iron Mask, and others. The mining world began to take notice of these remote diggings, and Rossland’s population jumped to 3,000 by the year’s end. It was then a sprawling camp of shingle shacks, log cabins, and canvas tents, stretching across the head waters of Trail Creek, and to the astonishment of Coastal residents, the fifth largest city in British Columbia.

Frederick Augustus Heinze, of New York and Butte, had been invited to come to Trail to duplicate his success in Montana. One of three sons of a prosperous Brooklyn dry goods importer, he had been educated in Germany and the Columbia School of Mines. He had come to the Montana copper camp as a young mining engineer of 19, to work for Boston mining corporation. The Butte copper mines were then the site of a bitter struggle between W. A. (later Senator) Clark, and Marcus Daly for control of the major mines. Operating quietly between these two giants, Fritz Heinze saw that there was an opportunity for a custom smelter, which, using the new cupola furnace technology he had learned in Europe, would smelt the ores from the small independent mines at a lower charge than Clark’s and Daly’s works. With the backing and participation of his brothers, Arthur, a lawyer,and Otto, a financier, the three of them founded the Montana Ore Purchasing Company and built their smelter. Shortly, Heinze’s investigation of inactive and abandoned mines suggested that ore bodies remained in them which had not been developed. The Montana Ore Purchasing Company put a down payment on the Rarus mine and quckly turned it into paying entrprise, feeding their smelter. Heinze’s ability to locate ore bodies in supposedly worked out properties made him famous in Butte; he was either the luckiest or the most knowledgeable of its mining enginers.

British Columbia mining men had heard of his remarkable success in Butte and invited him to British Columbia in 1894. A quiet examination of the Rossland mines persuaded him that here was an opportunity for a smelter. His brothers raised the $300,000 required, largely from the Heinze family, and he approached the Spokane Colonels offering to buy the Le Roi. But when he could not produce the substantial down payment they insisted on, the deal fell through. He then sucessfully negotiated a contract to smelt the Le Roi ore. Using Rossland’s A.E. Humphries as his agent, he secured a site for his smelter and an association with Colonel Topping in the Trail townsite company.

As soon as the agreements were signed, he got underway at once, ordering 25,000 cords of firewood for roasting the ores, and 50,000 bricks to be made locally for the chimney and furnaces. The tramway to the mines had to be built as quickly as possible. If D. C. Corbin should get his rails to Red Mountain, Heinze would have to bid against him for those Red Mountain ores.

Smelter construction got underway on September 13, 1895. With the lack of adequate transportation facilities to bring in smelting coal at a reasonable price, Heinze prepared to roast his ores with cord wood on open piles and then smelt the mix of iron, copper and sulfur in a single furnace with charcoal. It was not efficient, but the ore was rich and the process cheap. Speed was essential, for a month after Heinze began building his smelter, the Hall Mines Syndicate began construction of its copper smelter at Nelson, where coal and coke could be delivered cheaply from U. S. sources on Corbin’s Nelson and Fort Shepherd line.

Quickly, Heinze bought up Peter Larsen’s proposed tramway company with its charter to give him the right to acquire right of way through public lands and give himself uncontested access up Trail Creek Gulch an ownership of Larsen’s pile of rails down on the beach. An once he set his railroad superintendent, F. P. Gutelius, to surveying a scratch narrow gauge tramway up Trail Creek to the mines.[i]

Down at Northport, Daniel Corbin, stalled by the prohibition to enter the Colville reservation, was running out of time. The Canadian charter he had obtained for the 9-1/2 miles of his line in Canada had a time stipulation: construction must commence immediately or the charter would be canceled. He appealed to the government for a time extension. It was denied. He appealed for permission to build his line as a cheaper narrow gauge. The citizens of Rossland protested this niggardly maneuver. Trail was building a narrow gauge line; they insisted on standard gauge, as the charter specified. The government agreed and denied this request as well.

Frustrated and desperate, Corbin sent his engineer, E. J. Roberts, and a grading crew to Rossland in the summer of 1895 with instructions to begin grading out of Rossland down Little Sheep Creek toward the border.[ii]

Heinze was not deterred. By November 9, 1895, the surveys for his Trail Creek Tramway were finished, and and on the 16th grading got underway with Nelson Bennett’s firm of Tacoma the successful bidder. Bennett had built the Stampede Pass switchback line for the Northern Pacific and was experienced in this sort of pioneer construction. He sent Charles King to Trail to take charge of the work.[iii]

As the news of Heinze’s invasion of the Kootenays spread, Van Horne of the Canadian Pacific, had to move, even though the company was short of cash. In September, 1895, just a month after Fritz Heinze had announced his plans for a smelter and tramway, Van Horne proclaimed his railroad’s interest. It was a defensive move for the CPR. His first concern was to keep James J. Hill and his Great Northern feeder lines out of B.C. and strengthen the CPR’s transportation monopoly into the Kootenays.

That monopoly had suffered two defeats, the first in 1893, when Dan Corbin built to Kootenay Lake at Five Mile Point and began serving Nelson and the Toad Mountain mines with his Nelson and Fort Shepherd line. Van Horne bought Colonel Baker’s B.C. Southern charter, the same that Dan Corbin had burnt his fingers on, but with the country in recession, there was no money to build the 200 mile line from Alberta that the CPR needed to secure the Kootenay traffic. Until the CPR could negotiate land grants and cash subsidies for the line, Van Horne had to bluff. To counter Heinze and Corbin at one stroke, he announced a new line, the Robson – Rossland Railway, to be built by the CPR. It would start directly across the Columbia from the Robson docks of the Columbia and Kootenay, and would run down the right (west) bank of the Columbia to Sullivan Creek. From there it would begin a 3 percent climb to Rossland, contouring around the mountains, and entering the town from the east, to link all the producing mines in one, wide loop. As an insulting afterthought, five miles north of Rossland, a minor spur would be run down to Heinze’s smelter to supply his works with Crowsnest Pass coal and coke.[iv] Once the CPR line was built in from Alberta to connect with this line, he would cross Hill’s and Corbin’s lines with his own, and counting on government support, would freeze them out.

The second defeat came sureptitiously in 1894, when the locally chartered 29 mile narrow gauge line, the Kaslo and Slocan, building west from Kaslo to the silver- lead mines at Sandon, obtained quiet backing from Jim Hill. Hill did not want to add the narrow gauge to his Great Northern lines, but he did want those ores to move out of the Kootenays over his Bedlington and Nelson branch to Bonner’s Ferry and his main line. Financial control of the little K&S ensured this.

Fritz Heinze rightly assessed Van Horne’s Robson – Rossland line as a bluff. It would be several years before the CPR could bring a line in from Alberta. But when it did, he knew he would be in a desperate squeeze between two hostile railways, the CPR and Dan Corbin’s SF&N. In a bid to create his own outlet, he announced, on December 21, with his graders at work on the tramway, that he intended to apply for a provincial charter to extend his narrow gauge railway out west from Rossland all the way to Penticton in the Okanagan valley.[v]

Then he went to work on Dan Corbin, whose men were blasting their way around the narrow granite ledges southwest of Rossland. Posing as a sworn enemy of the CPR, Heinze wanted Corbin to abandon his plans for his Red Mountain Railway. The CPR was hostile to them both, he told Corbin. See what it was doing to keep his N&FS out of Nelson. It was in both their interests to combine in order to be strong enough to resist the CPR when it came. If, instead of building his difficult Red Mountain Railroad from Northport up Big and Little Sheep Creeks, Corbin would build a branch from his Nelson and Fort Shepherd Railway at Sayward up the east bank of the Columbia to a point opposite Trail, his cars could be ferried across to Heinze’s tramway. He would three rail his Trail Creek Tramway, Fritz Heinze promised, so that Corbin could supply him with the coal and coke he would need. It sounded eminently reasonable; the Trail Times trumpeted its advantages. Trail would have a direct, standard gauge connection to Spokane and the two transcontinentals there. The smelter would have inexpensive coal and coke from Roslyn on the NP line, rather than the costly CPR coal from Vancuver Island, a supply that could be shut off by the Columbia freezing in winter.[vi]

Dan Corbin was not persuaded. Heinze was keeping the ore haul from the mines exclusively for his own line, he observed. Heinze upped his offer. He would have Gutelius run a 3 rail line down Bay Avenue to a rocky bluff, the best site for a Columbia River bridge (in fact the site of the present Yellow Bridge). Here Corbin could bridge the river, a shorter and easier crossing than at Northport. Corbin still refused.[vii] Well, he would build the bridge himself, Heinze offered. Dan Corbin still refused.

As Corbin continued hostile, Fritz Heinze knew that by the time the Red Mountain Railway and the CPR line from Alberta were complete, he would have to have his own rail connection to coal and to the markets for copper, or his adversaries would crush him. In mid construction, he changed the name of his Trail Creek Tramway to the Columbia and Western Railway and prepared to win the backing of those Vancouver and Victoria merchants who were still agitating for a “Coast to Kootenay” rail line.

In March, 1896, the news came that the American President had signed the bill giving Dan Corbin the right to cross the Colville Reservation with his rails. Corbin at once assembled his crews, and using a ferry to cross the Columbia at Northport until his bridge could be built, he had them begin grading up Big Sheep Creek.

Heinze pushed on. He announced bombastically in the Trail Creek News that,

“The smelter will start up in about a month and and will handle the entire ore supply of this district, taking the whole output from the Le Roi and Iron Mask. We now have 45,000 tons of Le Roi ore on hand valued at $30 a ton and will have 125,000 to 150,000 tons of ore in the smelter constantly. We keep on hand supplies of 100,000 cords of wood and $50,000 worth of coke of which we use three carloads a week. We use from two to three hundred cords of wood daily, the production of which will give employment to a small army of men. We propose to do custom work and the poor man can bring his one ton of ore and have it treated as cheaply as can the rich man with his thousands of tons.” [viii]

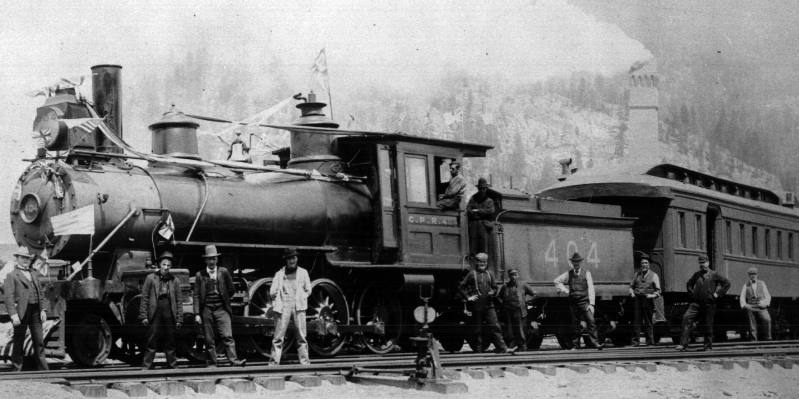

After this boast, Heinze had Herman Bellinger, his smelter manager, begin an outdoor roast of Le Roi ores brought down from the mines by wagon. His graders were nearly half way to Rossland. The sternwheeler Arrow brought a barge down from the Canadian Pacific at Revelstoke on March 26, 1896, with a used narrow gauge locomotive and four wooden coal cars from the Alberta Railway and Coal Company. At the mouth of Trail Creek, where Larsen’s rails were lying, the locomotive was carefully levered off the barge and onto a hastily built line of Larsen’s rails and hand hewed ties. A team of horses pulled the fifteen ton locomotive and the cars up to a small yard Gutelius had improvised under the Bay Avenue bridge over the Trail Creek delta.

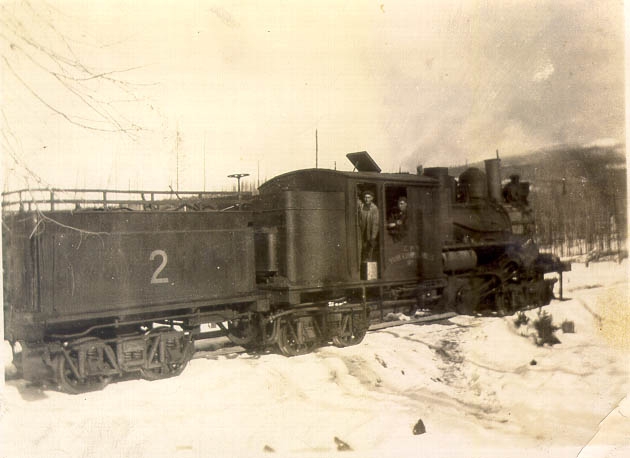

Before it could be operated, No. 2, a fat boilered Hinkley 2-6-0, had to be converted to wood firing. No. 2 was turned out by Hinkley in Chicago in 1879 as an 0-6-0, with 12 x 18” cylinders and tiny, 31 inch drivers, giving it a tractive power of 13,000 pounds. No 2 was converted to a Mogul by the Alberta Railway and Coal Company with the addition of a pilot truck. It ran on the Great Falls and Canada ern narrow gauge line, hauling Alberta coal down to the smelter at Great Falls, Montana. This line, known as “The Turkey Trail,” was bought by Jim Hill when his Great Northern, pushing west, encountered it. In the 1890s it was standard gauged and its 3 foot equipment was being peddled all over the Northwest to the Kaslo and Slocan, the Trail Creek Tramway, and other narrow gauge lines.

In Trail a big Radley and Hunter stack with its wide spark arrestor netting was applied to No.2 . This was obligatory for all wood burning locomotives to reduce the hazard of sparks setting wildfires along the line. Wood burning grates replaced the coal grates in the firebox, and high sideboards were built on the tender to carry enough wood for a thirteen mile trip up to the mines. The bearings needed to be checked as well, since the machine had been out of service for some time.

In the small yard a section of track was greased and steam was raised in No. 2 by fireman, Sam Stingley. The Hinkley, in charge of W.H. Garlock, former Master Mechanic of the Seattle, Lakeshore and Eastern RR., was then run onto the greased rails and chained securely to two yellow pine tree stumps still present in the townsite.

To the intense interest of the idlers and small boys lining the rail of the bridge above, the throttle was opened and No. 2 spun her drivers on the slippery rails, lunging at the restraining chains and shooting a plume of steam and blue wood smoke high into the pale April sky. Mechanic Garlock bent close to the churning drivers and listened for the pound of a loose bearing. The throttle was closed. He pulled the cotter pin from an adjustment nut and tightened it just a fraction of an inch, then replaced the pin. He signaled for power; the drivers spun again, and Garlock bent to listen. Another adjustment was made. When all was well, he went through the same procedure on the other side. Bearings were tightened, the drivers spun, the valve settings checked, and checked again. In the days before roller bearings, the brass journals of the locomotive axles were coated with a film of anti-friction metal known as Babbitt, a low melting point alloy of tin, antimony and copper. Under load, this soft metal between the steel of the axle and the brass of the journal, formed a nearly frictionless metal film on which the locomotive rode. The bearings needed to be tightened to the point where the Babbitt was snug against the brass of the journal, but not so tight that the soft metal would overheat, melt and throw out. It was a delicate adjustment and could be made only by judging the sound and temperature of the bearing by ear and feel, as the wheels spun.

The tests went on most of the day. Superintendent Gutelius was laying out a steep and crooked railroad, and only a locomotive in perfect condition was going to be able to operate it. By late afternoon, No. 2 had passed all inspections, and the four wooden coal cars had had their coal boxes removed and been refloored by the carpenters as flats. Locomotive and cars were now ready to move ties and rails up the line to the track laying crews.[ix]

On April 1, 1896, after posing for photographs with Colonel Topping, Superintendent Gutelius, Frank Hanna and the Hanna kids, Trail Creek Tramway No. 2, with her four cars, was ready to begin laying track, following the graders up the hill at the rate of a quarter mile per day with Gutelius’ improvised tracklaying machine. A temporary track was first run up into the townsite from the beach where the barges would off-load more rails from Alberta and ties from the tie hackers up the river. From near the present intersection of Farwell and Cedar in Trail, the permanent track was begun, laid with standard gauge ties, and with the rails offset to allow for a third rail to be spiked down later, as Heinze had promised Dan Corbin. The grade ran up the right (south) side of Trail Creek on a 3 percent grade. At a collection of shacks known as Dublin Gulch, the grade of the creek exceeded a practical grade for a railway and the first switchback was laid at mile 0.8. The line reversed across the the creek and climbed its north bank on a 3.9 percent grade until it reached the top of the level bench where the smelter was under construction. Here Gutelius’ crews laid a wye and a small yard at mile 1.5. This was to be the headquarters of the Trail Creek Tramway, now officially the Columbia and Western Railway. An office was begun here with its second floor reserved for accommodations for President Heinze during the one week each month he spent in Trail.

The line reversed at the smelter wye, and now with six foot narrow gauge ties and no provision for a third rail, headed up the north bank of Trail Creek. At Annable, at mile 3.1, the creek rose to meet the little line and Gutelius’ grade crossed it on what has been measured today as a 4.8 percent grade. Gutelius, instructed by Heinze to get tracks up to those mines ahead of Dan Corbin, was building to the limit of his small locomotives’ capacity. The line crossed the creek above Annable on a 25 degree loop, reversing direction to climb out of the creek onto the second bench at Warfield, mile 4. A 25 degree curve is one on which a 100 foot chord along the curve intercepts a 25 degree central angle. This awkward method of designating the sharpness of a curve comes from the way curves are laid out by the engineers. A “hub” or center is chosen and lines of equal length run to every 100 feet of track to ensure the curve will be uniformly circular. Common practice on main line standard gauge railroads is to limit curves to under 5 degrees. A 25 degree curve on a grade severely limited a locomotive’s pulling ability. On a full half circle, and there were three of these 180 degree loops on the Trail Creek Tramway, the outside drivers of the little Hinkley had to turn nine feet, five inches farther than the inside drivers. This meant nine and a half feet of wheel slippage in negotiating the loop. On the following cars, the outside wheels had to slip as well, increasing the drag on the engine. To compensate for this, Gutelius reduced the grade on the sharp curves .04 percent per degree of curvature. This effectively reduced the grade on the 25 degree loops to 3 percent to keep up-bound trains from stalling.

At Warfield bench a second 25 degree loop reversed the line up Trail Creek again and it proceeded as it had from the smelter, up the north bank on a 4 percent grade until the creek rose to meet it at Tiger, mile 6.5. Here Gutelius crossed the creek and laid a switchback on a 25 degree curve. The line then backed around the granite nose of Lake Mountain into Tiger Creek on a 4.6 percent grade. Below the waste dumps of the Tiger and Crown Point mines, another switchback was set at mile 7.5 and called Crown Point. Reversing here, the line swung back around the nose of Lake Mountain again with two levels of track below it, and proceeded up the south side of Trail Creek.

At Carpenter’s, mile 8.8, it crossed Gopher Creek and the old Dewdney Trail, climbing through Joe Moris’ Homestake claim into lower Rossland at the Spitzee Mine, mile 10.5, where a mine spur was laid out. A passenger shelter was to be built here at Union Avenue for the residents of lower Rossland. At Cook Avenue, the line looped across Trail Creek for the last time and climbed east between Kootenay and Le Roi Avenues through the steepest part of town, to curl around Rossland in a counter-clockwise spiral. Author Peter Lewty, former Rossland resident, reports having found 12 x 12 timbers set vertically between the ties to hold the track to a piece of 4.8 percent grade. This may well have been done later by the CPR when the line was standard gauged.

At the corner of St Paul street and Le Roi Avenue, a station site was located on a lot donated by the Rossland Townsite Company. From this point the line had to be blasted through granite bluffs as it climbed into the upper part of town, crossing the Golden Dawn, Paris Belle and Golden Chariot claims amid the squatters of Sourdough Alley. Gutelius’ grade stakes were now marching into Dan Corbin’s land grant, though it is not clear whether Superintendent Gutelius knew this or not. Most likely, he set his stakes and left it to Fritz Heinze to settle with Corbin. Gutelius’ stakes outlined a wye to turn his trains on the small flat on Monte Cristo Street between Second and Third Avenues. From this flat, the stakes made a wide, climbing loop to the east, and then turned west on present Mc Lead Avenue, passing above the Great Western Mine. Continuing west, spurs were staked to the Enterprise, Virginia and Idaho mines. The stakes then turned up Centre Star (Acme) Gulch and indicated a high, curving trestle across it to the lower slopes of Red Mountain and the Centre Star mine at mile 13. The Le Roi and the War Eagle were higher up on Red Mountain, so to reach their ore bunkers, a high line branch was staked out, beginning back at mile 12.7 and climbing into the same Centre Star Gulch on a higher alignment. The gulch was crossed with a second trestle, this time on a 25 degree curve. Parallel to the lower line, but 200 feet higher, the high line reached the War Eagle at mile 13.2 and the Le Roi at mile 13.3, and the end of the grade survey.

The Trail Creek Tramway was engineered to climb 2400 feet in 13 miles with long stretches of 4 percent grade, several climbs of 4.6 percent, and two short pieces of 4.8 pecent. Nelson Bennett’s crews would lay out four switchbacks, Gutelius’ carpenters would have to build eleven timber trestles, and on those sharp 25 degree curves, ties would have to be cut to length and tamped in place to brace the curved rails against the mountain wall. It was a pioneering railroad, steep and crooked, with the prudent consideration that all mines have a limited life and that the railroad might only be needed for five or six years.

Down at the Columbia River, another barge from Revelstoke brought in Locomotive No. 1, an Identical Hinkley 2 -6 -0, from the Alberta Railway and Coal Company, and more cars. With Nelson Bennett’s men well up the gulch, digging and blasting grade, and Gutelius’ home-made track layer following with rails and ties, the little railroad was underway. In Trail, track was laid down the center of Bay Avenue to the south end of town where a sawmill which was cutting ties and timbers for the line. From the south end of Bay Avenue, a track angled down the riverbank with a switchback to keep runaway cars from plunging into the Columbia, and reversed down to the extreme low water level. Here the transfer for passengers and freight from steamers and barges was made. The original scratch line at the mouth of Trail Creek was taken up, since the spring floods would wash it away in any case, and its sole purpose had been to secure Larsen’s rails on the beach at that point.

Fritz Heinze had renamed his Trail Creek Tramway the Columbia and Western Railway to attract support for a rail outlet to the coast which would make his Trail smelter independent of both Corbin and Van Horne’s lines. He had his engineers survey a line running from the Le Roi mine west, contouring around the slopes of Red Mountain and into the head waters of Little Sheep Creek, maintaining its elevation along Mt. Roberts, OK Mountain, and crossing the Rossland Range through the pass between Mt. Sophie and Record Ridge. From there it was to hold its elevation as it contoured to the head of Big Sheep Creek and then back south to cross the 5000 foot Santa Rosa summit, and down to Christina Lake on the Kettle River. The line would have been 55 miles long, most of it snaking around the ridges and canyons of Big Sheep Creek, a fearfully cut up country where railroad construction would be extremely costly. Once in the Kettle River Valley, his line was to use Dan Corbin’s route to Midway, Rock Creek and over the Rock Creek range to Penticton.

The Trail Creek Tramway had been built under Peter Larsen’s Trail Creek and Columbia River charter without land grants or subsidies. But now Fritz Heinze intended a major railroad, and needed a more liberal Provincial charter which would grant him public lands along the right of way to sell or mortgage to provide the funds to build the line. His methods demonstrate his mastery of public relations.

The charter he wanted was nearly the same as that which had been refused Dan Corbin a few years before. Fritz Heinze, however, young, handsome and personable, seemed able to charm the very men that cold, grim, Dan Corbin had offended. Heinze’s campaign opened with an announcement that he would build a line from Rossland to the newly discovered copper-gold deposits above Greenwood, the claims that the young Jay Graves was being invited to invest in. A smelter had been built in Vancouver in 1889, but was languishing for lack of ores. Heinze led the owners to believe, that with his railway, they could bid for those ores. His line would carry them to Penticton where they could be put on the CPR steamers to the Shuswap and Okanagan Railway at Okanagan Landing, and from there they would move to the CPR main line at Sicamous.

The Vancouver press was intrigued but suspicious. Heinze’s proposal sounded to them like Captain Ainsworth’s scheme warmed over. Or Dan Corbin’s proposal under another name. But Heinze’s line did have one thing that the Canadians could approve: it did not have a Spokane connection. Heinze said he would connect his line at Penticton end to end with that “Coast to Kootenay” line if it were built. This would tie the Kootenays to Vancouver, not Spokane. At this enthusiasm built. When public sentiment had swung his way, Heinze flashily presented himself at the Legislature, young, handsome, confident, impeccably tailored, and radiating charm.

In Victoria, Heinze was persuasive. He merely wanted a charter, he told the members, not public money. He invited the members and their wives to a great dinner at the Driard Hotel. There was food and wine and oratory. Fritz Heinze presented himself as a champion against the CPR’s greedy scheme to capture the Kootenay traffic for the hated East . Why, he said, if he got the charter, he would build a copper refinery in Vancouver, and ship his copper matte there for finishing, and not to Montana as he was presently doing.

The combination of provincial patriotism and profit was as persuasive for Fritz Heinze as it had been for Captain Ainsworth. He got his charter, where Dan Corbin had not. Confident they were doing the right thing, the Legislature gave him a land grant as well. Even further, as a sort of trophy, he got Lieutenant Governor Dewdney, the man who had contracted the trail, on his board of directors.

Yet, when the effects of fine wine and patriotic oratory had worn off, the legislators found themselves somewhat embarrassed by the immense tracts of land they were handing to this dandified American. As an afterthought, they required Heinze to post a bond of $50,000 that he would actually complete his railway to Penticton by 1900. Cannily, Heinze gave them a $50,000 mortgage on his uncompleted tramway, now grandly called the Columbia and Western. Much later, Heinze candidly admitted, “I went down there prepared to spend $50,000 among them, and all it cost me to get my bill through was $240 for a good dinner at the Driard.”[x]

Some British Columbians refused to be charmed. They began asking how their legislators had managed to give away such valuable blocks of land for a promise and a mortgage on an uncompleted railway. All admitted that there was a desperate need for a railway across the southern part of the Province, one that would funnel its trade to Vancouver. But once again, their legislature had handed the project to an American. Captain Ainsworth had tried to capture the Kootenays for Portland. Dan Corbin was trying to grab its trade for Spokane. The Canadian Pacific appeared ready to snatch it for Winnipeg and Toronto.[xi] Now here was this glib fellow, Heinze, who said he wanted only a charter, but is already back in town asking for a cash subsidy.

The coast cities of B.C. were outraged by the Federal Government’s Crowsnest Pass agreement with the CPR, which promised a subsidy of $11,000 per mile for the Kootenay line if the CPR would reduce freight rates in Western Canada. This was seen in Vancouver and Victoria as an outrageous reduction in rates to the East, which it was, while rates to Vancouver and Victoria remained unchanged. Obviously, the CPR, in building just half way across southern B.C. to the mines would replace Spokane’s control with Winnipeg control. Vancouver and Victoria would have no share in the bonanzas. In angry response, Mayor Templeton of Vancouver, Dr. Milne of Victoria, and the Mc Lean Brothers, contractors, chartered the Vancouver, Victoria and Eastern Railway and Navigation Company in 1897 to build a line from Victoria to Sydney, on Vancouver Island, to operate a ferry service to Vancouver, and then lay rails on the Dewdney Trail route to the Kootenays. These were evidently men who had never seen the notorious Dewdney Trail, or they would not have seriously suggested putting a railroad on it.

The railroad alliance between Vancouver and Victoria would not last. The railroad was known in Vancouver as the “Vancouver, Victoria and Eastern,” while in Victoria, it was the “Victoria, Vancouver, and Eastern.” In the rest of the Province, it was the “VV&E.” Still, it was a B.C. attempt to challenge both the CPR and Dan Corbin with a locally owned railroad, serving local interests. Heinze quickly responded. He would join his Columbia and Western rails to the VV&E at Penticton if they would build east to meet him.

To continue building his Kootenay Empire, Heinze now wanted access to the silver-lead ores of the Slocan and of Kootenay Lake for his smelter. He intended to install lead furnaces and capture those ores which were going to Jim Hill via his Kaslo and Slocan narrow gauge railway, and then by water to his main line at Bonner’s Ferry. But access to the Slocan Mines was by the CPR’s Columbia and Kootenay Railway from Robson to Nelson, and the CPR was implacably hostile to him. So, in an effort to persuade the CPR to allow Slocan ores to be shipped to him via the Columbia and Kootenay line, he invented a fictitious railroad, the “Columbia River and Kootenay River RR.” He had the cars being shipped to him from the Alberta Railway and Coal Company lettered, “CR&KRRR,” knowing the word would quickly reach Van Horne. Of course, the CR&KRRR never existed. It was a pure bluff. But Fritz Heinze was a Brooklyn boy with a wild sense of humor and a pugnacious self confidence. He awaited Van Horne’s reaction to this supposed railroad, by its title pretending to parallel the Columbia and Kootenay line. The Pilot Bay smelter on Kootenay Lake had failed. The Hall Brothers were smelting their Silver King copper -silver ore at Nelson. The CPR wanted the coal and coke haul from Vancouver Island, and the smelter matte haul out via the Columbia and Kootenay line to Robson, by steamer to Revelstoke, CPR rail to Montreal, and via ship to Swansea, Wales where it would be refined.[xii] By threatening a rival railroad to bid for the Silver King ores, which being copper with silver, he could smelt in Trail, Heinze seems to have been bargaining for a favorable rate on Slocan ores moving west on the Columbia and Kootenay to the steamer connection to Trail. Van Horne, however, was not a man to be bluffed.[xiii] He instituted a wholly exorbitant rate on Slocan ores moving to Trail to make sure no mine owner could make a profit contracting his ores to Heinze. Then he secured the ore haulage contract to the Hall Brothers’ smelter from the Slocan district for the CPR’s Columbia and Kootenay Railway which now had a branch to Slocan Lake and the mines.

On March 12, 1896, Heinze’s hastily built Trail smelter was blown in with Le Roi ore, wagon-hauled down the mountain. On April 2, as the first rails were being laid on the Trail Creek Tramway, the first shipment of 20 tons of copper matte from the smelter was trundled aboard the steamer, Lytton, for Northport where Dan Corbin’s line would start it on its way to Heinze’s copper refinery at Butte.[xiv] The Trail smelter was a crude operation, fed with cordwood rafted down the Columbia, and then hauled up the steep, high back to the smelter from the river. There were no electric motors. A main steam engine, its boiler wood fired, supplied all the power for the furnaces, mill, sampling works and crushers with a 2 inch rope drive. Power transmission technology, before electricity became available, depended on endless rope drives from the power house, running overhead to the various buildings where the moving ropes dived through the roofs to the grooved sheaves inside that turned the machinery. A rope splicer was present at all times to mend breaks in the rope which were frequent.[xv] The water jacketed blast furnace was fired with coke which Heinze had to bring in from the coke ovens on Vancouver Island via rail to tidewater, ship to Vancouver, and CPR rail to Revelstoke. From there it came down the Columbia through the lakes on barges to be transferred to the narrow gauge cars at Trail. In winter, when the Columbia froze, coke was obtained from Roslyn in Washington via Dan Corbin’s line, put on sleighs at Sayward and hauled up the ice road to East Trail where it was ferried across the river.[xvi]

Once Heinze’s smelter and the Hall Brothers’ smelter in Nelson, began producing copper matte on a continuous basis, the competition for Kootenay traffic became intense, with announcements of great projects being made monthly in the newspapers. An American company was proposing to build a smelter at Robson or at Blueberry Creek on the CPR’s proposed Robson – Rossland line, the Rossland Miner reported.[xvii] Another was rumored to be built at Northport. But Heinze was still in the lead. His Columbia and Western charter had been issued that May, and he announced that the Directors of the Railroad would be himself, of New York and Butte, Frederick Ward, of Rossland, Chester Glass, a Spokane lawyer, and the ornamental Lieutenant Governor Dewdney.

Sometime that spring, Heinze’s engineers convinced him that it would be impractical to build west out of Rossland over Sophia Mountain and in and out of Big Sheep Creek to reach the Kettle River Valley. They suggested a route from Trail up the west bank of the Columbia to a point across the River from Robson and then west, climbing the bluffs along the south shore of Lower Arrow Lake to Dog Creek which could be followed to Mc Rae Pass, a lower crossing than Santa Rosa Pass. From there the line could descend down Mc Rae Creek to Christina Lake. The line would be longer than the Santa Rosa line, but would have easier grades and but one summit. Heinze was more concerned with blocking the CPR than with grades and passes. He accepted the engineers’ proposal chiefly because it preempted the CPR’s Robson -Rossland line; if the Canadian Pacific wanted to reach Rossland it would have to do so over his rails.

The CPR, after the disastrous floods of 1894, had been obliged to rebuild much of its main line and replace weakened bridges in B.C. Desperately short of funds, announced that it would not build its Robson-Rossland line that year, as it had promised. Instead, the public was told, it would build to Trail instead, and three rail Heinze’s Tramway to Rossland to have its standard gauge cars pulled up the hill by Heinze’s narrow gauge locomotives. This seemed to be a feeler put out by Van Horne to learn whether Heinze would consider an alliance with the CPR against Dan Corbin whose men were steadily grading up Little Sheep Creek, closer and closer to Red Mountain.

In Rossland, the Miner reported on April 25, that the blasts of Corbin’s graders could be heard daily from the west, while from the east, the whistle of Hinkley No. 2 could now be distinctly heard as it bustled up and down the track in the canyon below, forwarding timbers, ties and rails to the track gang.

As the graders neared the Rossland townsite, the principals in the Rossland Townsite Company broke a promise, and demanded that Heinze pay for the land his rails were to cross. This infuriated Fritz Heinze, who had obtained a verbal agreement with the Townsite Company the year before when they were encouraging him by any means they could, to build his tramway. Now, with the tracks actually marching up the gulch toward their town, greed took over; they demanded $5,000. Heinze swore and blustered. He threatened to route his line east and north, circling outside the townsite, and put his Rossland station up on the Enterprise Claim, far above the business district. The Townsite Company countered with an offer for a station lot at the corner of Victoria Avenue and Spokane Street, which was far below the business district. A compromise put the station half way between the two extremes, at Le Roi Avenue between St Paul Street and Monte Cristo Street. This was on the original survey and the grading could proceed as planned.[xviii]

But further trouble manifested itself. As his graders entered the townsite, Dan Corbin, whose own graders were considerably behind Heinze’s, obtained an injunction from the court to prevent Heinze’s men from trespassing on his grant lands (everything north of First Avenue) with their grade. Heinze had brashly ignored Dan Corbin’s ownership of these lands when he had Fred Gutelius make the original survey, counting on his own negotiating skills to somehow wrest a permission from Corbin. Now, in a race to Rossland, Corbin was his adversary, and would use any method to delay the Trail Creek Tramway from completing its line. Fritz Heinze had to approach Corbin once again with an offer on that Sayward to Trail line to try to get him to lift his injunction. Heinze promised to build a three rail line from Trail to Sayward, and guarantee Corbin a share in the Trail traffic if only his graders were allowed to proceed. Corbin, not knowing Heinze that well, agreed. Heinze could build his track, he promised, and then, with his habitual thin smile, he exploded a bomb under the young man. It would not matter, he told Heinze, he was planning to build his own smelter at Northport; the Le Roi Company had already promised him their ores.[xix]

At this news it became more than ever essential for Heinze to build his C&W connection to the Coast.[xx] With the Hall Mines smelter in Nelson in operation, and with a greater capacity than his own, and now with a third smelter planned for Northport, it was going to be extremely difficult to dominate the Kootenay mining industry unless he could connect himself to Vancouver.

With Corbin’s injunction lifted, Charles King’s graders moved onto the heights above Rossland and finished their work. The track gangs, working behind them, laid the last rails the first week of June, 1896 at the Le Roi Mine and a “Last Spike” celebration was held. Townspeople came up on foot and in buggies, and every small boy in Rossland was there with his dog. Colonel Topping was present on his white horse, and his partner, Frank Hanna, in a new suit. Fritz Heinze, looking like a college freshman, was in charge. The gentlemen of importance removed their coats and hung them on convenient posts. In their shirtsleeves, they drove the final spikes, the sounds of their hammer blows echoing above the growing town, already spreading beyond its platted townsite. From over to the southwest, the rumble of a blast was heard. E. J. Roberts’ men were down in Little Sheep Canyon, chewing at the stubborn granite, ten feet at a blast. The Canadians, a minority in the crowd, grinned; it would be months before the American railway arrived. Heinze had won the race.

On June 6, 1896, the inaugural run was made. Locomotive No. 1, another Hinkley 2-6-0, was coupled to three boxcars which had windows cut in their sides. Inside, the cars each had a double bench down their centers, the passengers sitting back to back, facing outward, feet braced against the sides of the cars for what was expected to be a rough ride. It was a crisp morning and stoves were lit in the makeshift coaches to keep everyone warm for the trip up to chilly Rossland, 2300 feet above. Every seat was taken when No. 1 whistled off and moved down the center of Bay Avenue where crowds were gathered on the wooden sidewalks and people waved from upstairs windows. At Farwell street the 3.5 percent grade began and the train began its ascent of Trail Creek Gulch. At Dublin Gulch, the switch was thrown and the Hinkley backed its train up the switchback to the smelter where blue sulfur flames flickered on the piles of roasting ore, and thick, yellow fumes swirled around the train. The train reversed and climbed into Trail Creek Gulch again. Alongside, on the wagon road, teamsters scowled and cursed. They were hauling their last loads of ore from the Le Roi. In the following days they would move down to Bossburg or Marcus, Washington where work was to be had hauling mining machinery and supplies to Jay Graves’ new camp in the Monashees to the west.

Up at Rossland, on the granite bluffs east of town, men were watching with spyglasses, following the progress of the tiny train below and checking their watches. At moments the cars were visible through the trees, but for the most part, a moving column of blue wood smoke sifting through the firs was the only indication of the event.

Up on the Lake Mountain switchbacks, the passengers crowded the right hand windows for a look down on the roofs of their houses, a thousand feet below. On the crinkled surface of the Columbia, the Lytton, backing out into the stream, looked like a skittering water bug. As they backed into the tail track of the Tiger switchback, the crew of the Tiger mine, high above them, let off a celebratory blast of black powder to mark the occasion, and cheered the tiny Hinkley.

The sidewalks and wooden steps above Le Roi Avenue were crowded with onlookers when the train entered the Rossland townsite, crossing Earl, Spokane, Washington and Queen Streets, and coming to a halt at the new St Paul Street Station. The whistle blew, fireworks were let off, salutes were fired from every sort of firearm, and all made their way up the steep Rossland streets to a monster celebration at the Allen Hotel, complete with whiskey-garbled speeches and a barrel of phlegm-loosening punch, American Style. For, small as it was, this was an American railroad, American owned, American built, and operated by American railroaders. The Canadians, on the fringes of the crowd, let the Americans have their calithumpian celebration. Now, they believed, Canadian Pacific would have to come to Rossland as well. And it would bring Canadian capitalists from Montreal and Toronto to buy back their mines, it was hoped, from the Yankees.

The ore trains began service on the 16th. The little Hinkleys could handle no more than eight cars each. On the loaded trips down the mountain, with only hand brakes, the brakemen stood between the cars, with a foot on each, where they could apply brakes on two cars at once by using the leverage of a pick handle to twist the brake wheels. Three ore trains ran each day, plus three passenger trains. [xxi] The Hinkleys were pressed to the limit, and in December, Heinze sent Master Mechanic Garlock to Utah, where the Utah and Northern had been standard gauged and the UP, its owner, now had yards full of narrow gauge equipment for sale. Most western narrow gauge lines were reequipping themselves from the U&N; some of the older locomotives were going for as little as $250. Garlock needed a powerful locomotive; he picked out another 2-6-0 which suited him. It was a Brooks locomotive of 1881, originally Kansas Central, No. 8. There has been some confusion about this engine among rail historians. Some have thought it to have been Utah and Western No. 2, another, smaller and earlier Brooks Mogul. Utah and Western No. 2 was Brooks construction number 227, of April, 1875, with 36” drivers. Trail Creek Tramway (Columbia & Western) No.3 was Brooks construction number 578, of 1881, with 14 x 18 cylinders and 42” drivers. The narrow gauge Kansas Central, which had bought this engine new, had been acquired by the Union Pacific, and in 1890 it was standard gauged. No 8 and the other narrow gauge equipment were transferred to other UP narrow gauge lines. No 8 does not show up on the Colorado and Southern or the Denver, South Park and Pacific, nor on any of the UP controlled Utah narrow gauge lines. It seems certain, then, that it went to the UP owned Utah and Northern. This would have been after the U&N roster of 1885 was published, so it would not show up there. The U&N was standard gauged in 1887, and its three foot equipment put up for sale. The author’s conclusion is that C&W No. 3 was found among those locomotives stored for sale at Pocotello, Idaho, or Salt Lake City.[xxii]

In addition to No.3, Garlock bought 11 flat cars, 6 boxcars, a first class class coach and a private car. This last was the Brigham Young family’s car, dating back to the days when the Mormon Church owned the Utah and Northern and a number of other narrow gauge lines in Utah. The car was reportedly decorated inside with paintings of angels, cherubs and seraphim. In Trail it was rebuilt to suit President Heinze’s much more worldly tastes, with “one half fitted up as a drawing room with lounges.”[xxiii] One may suppose that a “drawing room” for Fritz Heinze would have included a poker table, chip racks and a bar, appurtenances that the Trail Creek News chose not to specify. Eyewitnesses testify, however, that the angels and seraphim were retained to look down on the antics below and to gratify Fritz Heinze’s irreverent sense of humor. In December, the private car made its first run with the contractors from Butte who were bidding on the C&W extension to Robson West.

Once the Trail Creek Tramway was in operation, Heinze ordered a second furnace for his smelter to increase its capacity. He went to the Spokane Colonels to negotiate a long term contract for Le Roi ore before Dan Corbin could complete his line. The Colonels refused. They believed he was overcharging them for smelting their ores. Dan Corbin had just made them an attractive proposal: one third of the Northport townsite if they would build a smelter there. Henceforth, the Colonels told Heinze, they would mine and smelt their own ores. The CPR, building slowly up the east side of Crowsnest Pass, and not likely to arrive in Nelson for another two years, tried to stay in the game by announcing a smelter to be built at Blueberry Creek, half way between Trail and Robson.[xxiv]

Heinze, with his revised plans for the C&W, went back to the B.C. Legislature for a cash subsidy for his line which his engineers had told him was going to be fearfully expensive to build. His charter gave him a grant of 10,400 acres of public land per mile of narrow gauge railway built, or 20,000 acres if standard gauge. The land grants would be handed over as the track was completed, and then could be mortgaged to pay the contractors. Now he got an additional grant of $4,000 cash per mile. This would still not be enough. In the summer of 1896, taking the ornamental Governor Dewdney along, he sailed for England to try to raise money to build the C & W. In England, he showed his prospectus claiming his tramway was grossing $25,000 per month and his smelter, $100,000.[xxv] Governor Dewdney was displayed as the obligatory “Guinea Pig,” the sort of titled nonentity which gave Britishers confidence that their investments would be well looked after.[xxvi] However, even Governor Dewdney’s assurances could not convince British investors that a railroad from Trail to Penticton — “from nowhere to nowhere” as it was said, was anything but a backwoods pipe dream. Heinze and Dewdney returned empty handed, and Fritz Heinze mortgaged some of his Montana holdings for the funds with which to begin the first section of his Columbia and Western Railway, the line from Trail to Robson West, a steamer landing across the river from the Columbia and Kootenay terminal at Robson.

It was not until December, 1896, that Dan Corbin’s Red Mountain Railway was completed to Rossland. Heinze had a six months start on him and seemed in no hurry to fulfill his promise to build that three rail line to Sayward. He never did build it. No one did. Today it is still an absurd gap in the ore haul from tidewater, which is filled with a truck haul from the BN transfer at Sayward to the Cominco smelter.