CHAPTER FIFTEEN

RED MOUNTAIN: BOOM AND DECLINE 1900 – 1997

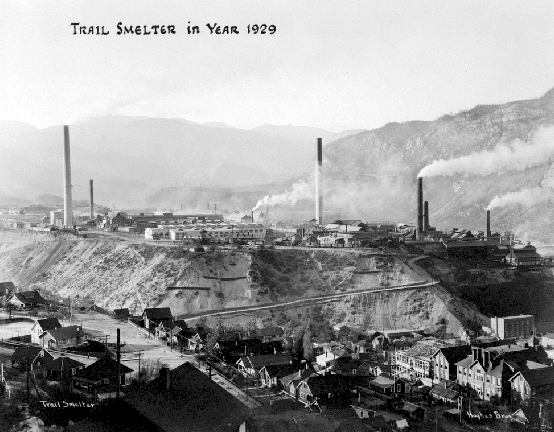

Trail Smelter 1929 – Photo Credit: wikipedia.org

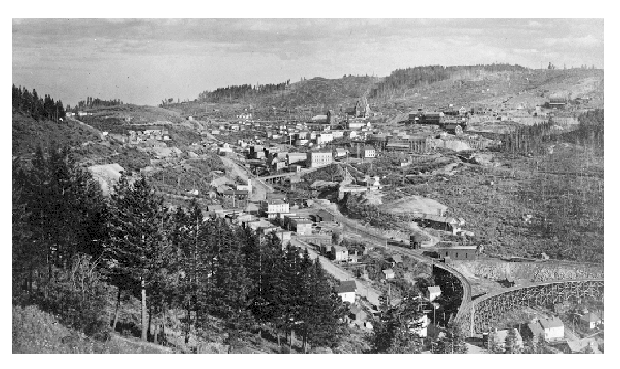

When standard gauging its Rossland line, the CPR moved the Rossland yards to a flat between Second and Third Avenues, extending from Washington to Butte. A commodious station was built on the site now occupied by the Rossland fire hall. On the north side of the four track yard, a freight shed was erected, and at the east end, near Butte, a two stall engine house. Alongside the yard tracks private interests put in a coal yard, a feed store, and a drayage warehouse. Down in the lower town at Cook Avenue, a roofed platform for passengers was built at the water tower. As in its narrow gauge days, this was still called “Union Avenue.”

With both the CPR and the Great Northern in town, their bitter rivalry was not long in breaking out. At the west end of Rossland, the Red Mountain Railway had a spur up behind the present museum which hauled ore from the Black Bear mine, delivered coal for its power plant, and timbers for mine props. Further east and some hundreds of feet up Red Mountain was the second class dump of the great Le Roi mine. The Northport smelter had installed a concentrating plant and now wanted that ore.

Accordingly, in the first days of November, 1900, the Red Mountain Railway sent out its engineers to stake out a line climbing west from the Black Bear spur to a switchback on the Annie claim. Reversing there, the line climbed back east to the Le Roi second class ore dump and on to the end of the CPR track at the War Eagle ore bunkers. This line would allow the Northport smelter to bid for both the Le Roi second class ore and for the War Eagle ores.

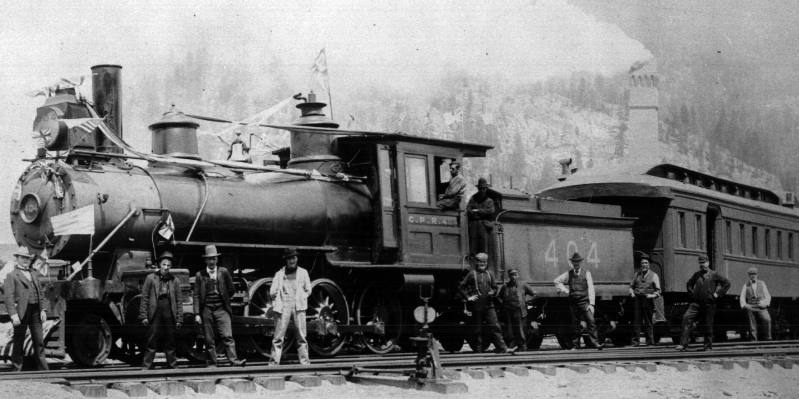

For once in its long life, the CPR moved with dispatch. On the Ninth of November, the train from Nelson brought a full crew of workmen, engineers, and their tools. The next morning, as the dawn sun was glimmering through the fog-shrouded town, the CPR men with teams and scrapers assembled at the War Eagle ore bunkers. Running west and slightly downhill was the line of Red Mountain survey stakes. After a careful sight through his instrument, the CPR engineer pronounced the Red Mountain grade suitable. At once the CPR crew began to grade it with shovels, picks, wheelbarrows and horse drawn scrapers. It was not until the next day that an outraged Red Mountain crew arrived from Marcus to find the CPR had graded their own line down to the Black Bear mine on the Red Mountain survey and were preparing to lay ties and rails

. Howls of indignation went up, but this was Canada, and no pistols were drawn. The Red Mountain telegrapher in Rossland sent out an SOS to Spokane. Spokane wired Jim Hill in St Paul. The mighty Empire Builder raged. His Spokane lawyers were roused from their beds at midnight and bustled onto a hastily assembled special train at the Spokane depot. They were to be in court in Rossland promptly at ten in the morning. On came the Lawyers’ Special, storming up the hill to Rossland, and screeching to a halt at the Spokane Street station. A squad of shivering and sleepless attorneys descended, and clutching their briefcases, hurried down to the courthouse on Columbia Avenue.

But, as they were to learn, the CPR was a power in Canada. The legal arguments were many, learned, and passionate. Still, the owners of the mining claims over which the disputed rails passed, raised no objection; they were quite delighted to have rails at their mine mouths. His Honour could find no injured party.

On December 14, the judge upheld the CPR rails and the Spokane lawyers departed. On the 16th, the Red Mountain capitulated, and connected its rails at the Black Bear with the CPR tracks. Both lines could now compete for ore from the Black Bear, the War Eagle, and the Le Roi second class dump. Belatedly, on the 23rd, the CPR published its “Notice of Application to Build a Branch Line to the Black Bear Claim.” That closed any legal loopholes, and the Red Mountain Railway resigned itself to the interchange track.

With the end of regular sternwheeler service, the CPR removed the tracks from Bay Avenue and the Trail station to a more central location at Cedar and Farwell (where the Super Valu market now stands). A wye was installed here to turn the engines. The War Eagle and Centre Star mines were bought in 1906 by the newly organized Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company (COMINCO) which began a policy of buying mining properties to assure the smelter of a continuous and predictable supply of ore. The Northport smelter was still bidding for ores and faced uneconomic shutdowns when they were not forthcoming. As Rossland entered the present century, the results of the early high grading days became evident. The Red Mountain mines had been opened in a virtual wilderness by the Spokane Colonels and Canadian Honourables when only the richest shoots of ore could pay their way to a railway siding by pack team or rawhiding.

In 1896 the ore shipped out ran an average of 1.45 oz. in gold, 2.34 oz. silver, and 40.9 pounds of copper per ton. That rich ore was worth $32.64 per ton. The charges at the pioneer smelters were high, between $10 and $14 per ton, reflecting the high cost of getting coke and coal to the smelters by the roundabout rail and water routes. Two years later, the average ore being mined contained only half as much gold, but owing to a doubling of the copper price, was still bringing a profit of about $20 per ton.

The Le Roi, hoisting twenty six carloads daily in 1901, could claim ore values of only $13.16 per ton. With the CPR bringing coal and coke directly from the Crowsnest fields, the smelter charges were more modest. Combined mining, haulage and smelting charges averaged just $10.72 per ton. This yielded a profit of $2.44 per ton, a tenth of what it had been three years earlier. $2.00 per ton remained an average profit for the red Mountain mines for some years thereafter. High grade ore shoots were still being uncovered from time to time; each was announced with great fanfare in the mining press. But breathless publicity was largely a device to bolster stock prices and keep investors buying. As the mines went deeper, the tenor of the ore steadily declined. Smelter managers sent ore buyers into the field to purchase ores with a high sulfur content which would reduce the amount of coal required in the furnaces. For this reason it was economic to bring in the bornite and chalcopyrite ores from Phoenix to blend with the lower sulfur Rossland ores. The much lower mining costs at Phoenix where the massive deposits could be worked with power shovels from huge glory holes, more than offset the cost of hauling these ores over the Monashees to Trail or around by Marcus to Northport.

With a progressive decline in the quality of ore as their mines went deeper, the Rossland mine managers blamed their inability to pay dividends on high labor costs.They refused to honor the legally mandated eight hour day, and instituted a change from an hourly wage to a contract system, paying their miners so much per ton or per foot of tunnel dug. The Rossland miners refused and struck on July 11, 1901. The strike was long and bitter, but eventually failed as the local union broke away from the Western Miners Federation in Denver, uncomfortable with its openly Socialist ideology. With the miners now on a contract system, the mine managers were no longer able to blame their failure to produce rich dividends on excessive labor costs. The truth was was that the Le Roi, the Centre Star and War Eagle had been bought from the Spokane Colonels at vastly inflated prices in the speculative boom of 1898. The ore being mined after 1898 could simply not pay the dividends demanded. General informed belief was that the miners had been scapegoated. The British Columbia Mining Record editorialized that the real reasons for the unprofitability of the Rossland Mines after 1898 were, “…the exaggerated anticipations on the part of investors; extravagance and incompetence on the part of the representatives of the investors” (the mine managers); “over taxation… and extensive swindling on the part of company promoters.”

To reduce mining costs Aldridge of the Trail smelter proposed uniting all the major producers into one company. All were interconnected underground; amalgamation would allow all hoisting to be done through one shaft, and a single compressor station and lighting works would serve all the mines. The owners refused, believing the proposal to be a CPR grab for monopoly control. Aldridge was persistent; he believed that if the CPR did not buy the mines, the Great Northern would.[v] Gradually, opposition weakened, except for Mc Millan, manager of the Le Roi. He was especially obstructive, attacking the condition for merger that gave the CPR all the haulage of the combined ores, and the Trail smelter all the treatment. Aldridge saw Mc Millan as representing Jim Hill’s interests. This was true. J.J. Hill, in far off St Paul, had been myopically buying shares in the declining Le Roi for the express purpose of preventing the CPR from getting hold of it, and denying Hill’s Red Mountain Railway of its traffic.

In 1905 Aldridge was able to buy the War Eagle/Centre Star (already consolidated) from the Gooderham-Blackstock families in Toronto for $825,000. With these and other purchases, the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company, Ltd. (COMINCO) was created in 1906. Cominco was capitalized at 5 million dollars, a wringing out of the excessive capitalization which had hamstrung the separate companies. It comprised the War Eagle,. Centre Star, the Trail smelter, The Rossland Power Company (an ore concentrating works), and the St Eugene mine, a lead-silver property in the East Kootenay which Aldridge optimistically expected to replace the Le Roi as the primary supplier of ore to the smelter. The St Eugene was largely owned by the Spokane Colonels. They had its manager, James Cronin, working his miners overtime in the months before the merger, a repetition of their 1898 stripping of the Le Roi, by removing as much of the high grade ore as possible to show a high valuation. The St Eugene, as a result of the Colonels’ manipulations, was assigned 49.8% of the new Cominco stock, while the War Eagle-Centre Star got 33.2%, the Trail smelter, 15.8 % and the unsuccessful Rossland Power Company 1.2%. Turning over their virtually depleted St Eugene mine to Cominco, the Spokane Colonels retired with half the Cominco stock, having fleeced the Canadians once again.

Five years later, the worked out St Eugene was abandoned to a few leasers to pick its bones foe what they could find. Cronin, when the deception was discovered, was unceremoniously removed from the Cominco board. Mc Millan of the Le Roi, doing Jim Hill’s bidding, refused to join the merger. But Hill’s intransigence could not save his mine. Five years later, in 1911, the Le Roi went into liquidation and was sold to Cominco for $250,000. As the supplies of copper-gold ores diminished in quantity and value, Cominco switched its interest to the huge deposit of low grade lead-silver ores of the Sullivan mine at Kimberly in the East Kootenay.

This had been another of the Spokane Colonels’ properties, but here they had lost their shirts. They had spent millions building a smelter to process its zinc-contaminated ores. Then the usually shrewd Colonels became victims of their own exuberance. Hiring by mistake, the brother of the engineer they had intended to employ, the smelter he built for them was an utter failure. They sold out to the Guggenheims’ American ASARCO combine. Asarco as well was unable to treat the Sullivan ores successfully, and Cominco picked up the mine nobody wanted in 1910 for $116,000. The separation of the troublesome zinc was finally achieved with a flotation process, and the Sullivan, together with the Bluebell (the deposit the Indians and Hudson’s Bay Company employees cast their bullets from in the 1840s) on Kootenay Lake furnished the bulk of Cominco’s ores until the 1970s.

Still, copper-gold ores continued to come down the steep and crooked rails from Rossland, though, after 1916 in diminished tonnage. By 1910, the CPR M4 series Consolidation locomotives were assigned to the Rossland run, and for these heavier engines the existing 60 pound rail was replaced with 85 pound steel. Rails on the tight 20 degree curves had to be braced against the weight of these engines with ties wedged between the outside rail and the embankment. On other curves the outside rail was cabled to an iron pin driven into bedrock.

Braking on the downhill runs was always a problem. The older cars with wooden brake beams often arrived at Smelter Junction with the beams so badly scorched they would need to be replaced before the car could be sent up the hill again. A judicious handling of the brakes was required so as not to burn off the brake beams and lose the train brakes. In the Twenties all steel gondolas arrived with steel brake beams and the problem was eliminated.

In the early years, the Rossland branch used tiny 4 wheel cabooses just 15 feet long. These had been built in 1907 and 1908. They lasted until the CPR banned 4 wheel equipment in the 1920s. They were replaced by standard plan cabooses which had been shortened by ten feet. A home made flanger, built on the single car truck, lasted well into the 1940s.

After WWI the end was in sight for the Rossland mines. They were following leaner and leaner veins down into the mountain, almost down to the level of the Columbia. A plan was mooted to drive a tunnel from Warfield to intercept the deep workings and allow the ore to come out near present Haley Park. This would have eliminated the need for trackage above Warfield. The tunnel was begun, but too late. The Red Mountain mines were nearing exhaustion and further expenditure was not justified.

The Northport smelter had closed after the war for lack of ore. On July 1, 1921, the last Great Northern train departed from Rossland and the Red Mountain Railway was closed. In 1922, the rails were pulled and a one lane gravel road graded, most of it on the old railway line. The great Columbia bridge at Northport was given a wooden deck for automobile traffic. It served, an increasingly shaky structure old timers remember, until 1948, when one span collapsed and a ferry had to be put in service until a new highway bridge could be built.

With the closing of the Phoenix mines in 1919 and the diminishing amounts of ore coming out of the deep levels of the Red Mountain mines, Cominco decided in 1929 to close its Rossland mines. The next year it ended its copper smelting operations, and smelted exclusively lead-zinc-silver ores from the East and West Kootenay. A good many of the Rossland miners found work in the Trail smelter, and a Rossland-Smelter Junction commuter coach was added to the 6:00 AM passenger train to Nelson. The coach would be dropped off at Tadanac, as Smelter junction had been renamed. On the return run from Nelson, the train would pick up the miner’s coach at 4:15 PM and haul them back up the hill to Rossland.

When the great depression struck in the Thirties, the demand for metals dwindled and many smelter workers were laid off. To assist these men, Cominco leased its Rossland mines from 1933 to 1940 to its laid-off employees. A truck dumping facility was established on Washington Street. The miners would truck their ore to the ramp and raise the body with a chain fall to dump the ore into the CPR gondolas. The ore cars ran again in the three times per week service the CPR maintained to Rossland.

A paved highway down the hill to Trail opened in 1937. The miners then established their own commuting bus service to the smelter, a fifteen minute trip, as compared to an hour by train. That year, all passenger service to Rossland was withdrawn. Still, the freight climbed the hill three times a week, as Rossland, high above the smelter fumes, became the favored bedroom community for Trail employees.

Conversion from coal to oil fired locomotives came in the late 1940s. In 1953, diesel locomotives replaced steam. In 1962 the line down the gulch to the Trail City station was lifted, and in March, 1966, the Rossland line was abandoned. Track was lifted down to Warfield where the Cominco fertilizer plant still requires regular freight service bringing in phosphate and potash rock for conversion into fertilizer with the sulfuric acid formerly wasted up the stack.

The Red Mountain mines and the steep and crooked line that served them, had outlasted Phoenix which had sunk into its own pits. Rossland today remains a thriving community, and the Trail smelter, one of the world’s largest, processes ores brought from Alaska’s North Slope to Sayward up those historic Spokane Falls and Northern rails. At the Sayward transfer facility, the ores are transferred to trucks for the remaining six miles to Trail. The failure of Fritz Heinze, in 1895, to keep his promise to Dan Corbin to lay track from Trail to Sayward is perpetuated today in that costly and irrational trucking operation.

The inexplicable failure of the CPR to underbid BN for the Alaska ore traffic, has ended the procession of heavy ore trains from Cranbrook to Nelson to Trail, and the line from Yahk to Warfield has been sold to its employees. The Canadian Pacific, reluctant in the beginning to enter the Kootenay-Boundary country, has hastened to leave it, abandoning its rail future to the always aggressive Americans. BNSF trains still call at the old Great Northern points, at Sayward, at Salmo, at Grand Forks, at San Poil, and Curlew. The departing CPR has sold the Trail Smelter, and pulled all of its track west of Castlegar. Kootenay rail transport is back to where it was in 1899.