STEEP AND CROOKED: THE MINING RAILROADS OF THE CANADIAN BORDER

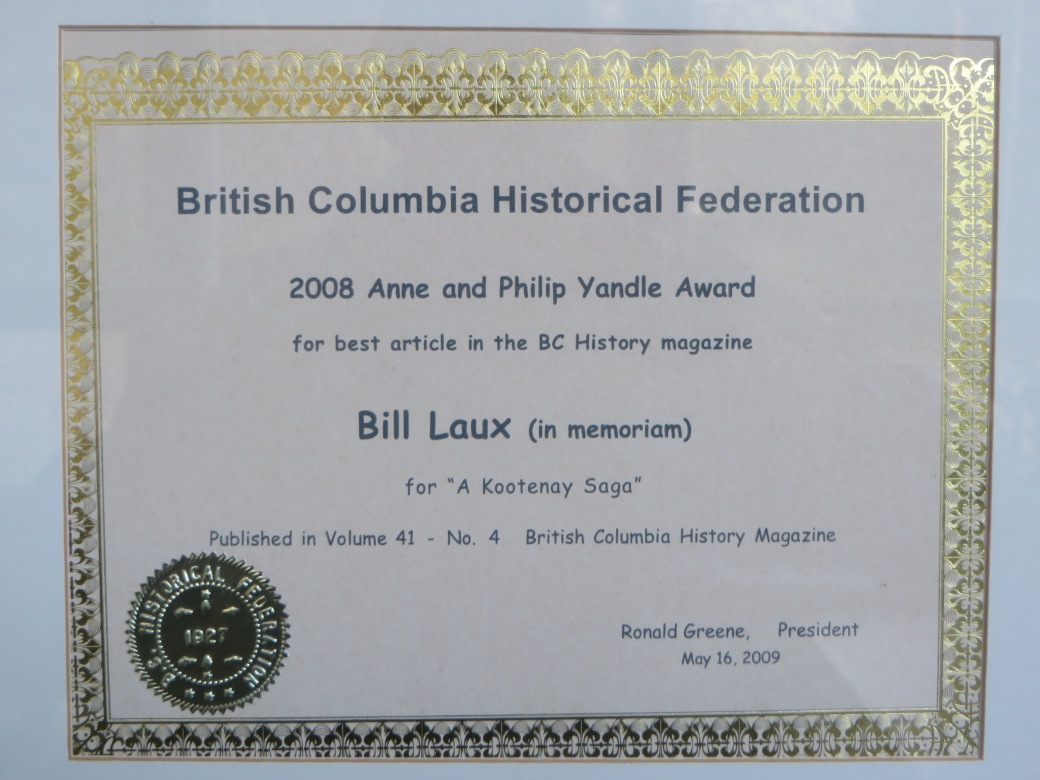

By Bill Laux

CHAPTER NINE

GRANBY 1895 – 1902

Jay P. Graves at the California mine on Red Mountain had held his breath in 1895 and taken the plunge. He bought into a pair of copper prospects on Knob Hill in the Boundary range of the Monashee Mountains a few miles north of the border. An old and trusted acquaintance, H.P. Palmerston, had come to him with a proposal. Palmerston had been offered one quarter of their claims on Knob Hill by the Greenwood prospectors, Henry White and Matthew Hotter, on a promise that he would raise development money. Palmerston was ill and unable to interest anyone in these remote claims. He sold his interest in them to Jay Graves.

Graves put his Spokane boarder, Aubrey White, a bookseller, to peddling stock in these claims to Spokane mining speculators in 1896. White could get no more than 10 cents a share; on the Spokane Mining Exchange they traded for just 5 or 6 cents. This was failing to raise enough capital to begin work, so Graves sold his house and moved his family into the Spokane Hotel. With the money from this sale, he hired Henry White, the original locator, to begin to clearing the forest from the claims and digging a trench to expose the top of the ore body. When the extent of the deposit had been established by trenching the shallow overburden of soil, Graves bought a boiler, a steam powered hoist and a steam pump to begin sinking a shaft into the ore. This machinery had to be hauled by wagon from Bossburg on the SF&N line to Grand Forks. Then a road had to be brushed out up to Knob Hill on the ridge top west of town. The claims that Graves had bought did not contain the rich, narrow veins plunging steeply into the mountain, as at Rossland. The trenching had showed that the copper was a large, saucer-shaped ore body just below the surface. How thick it was, no one knew. It was only 1 or 2 percent copper, but there was a great deal of it, and it contained minor amounts of gold and silver. A pit could be opened and the ore quarried cheaply out of the hillside. Still, more development money would have to be raised to determine the full extent of the ore body.

Graves had incorporated the two claims with 1,500,000 shares for the Knob Hill and 1,000,000 shares for the Old Ironsides. In 1899 he sent out Frank Hemmenway, a Spokane bank teller who doubled as a miner in the summer, to work with Henry White, trenching and taking samples for assay. Hemmenway had a sound reputation with Spokane mining investors, and his favorable report boosted the stock price on the Spokane Exchange. It also started a rush of prospectors and promoters to the Knob Hill discoveries. All those who had been too late to cash in on the Red Mountain bonanza now swarmed over Knob Hill, and claims were staked for several miles in all directions. The trenching White and Hemmenway had done on Grave’s Knob Hill claims suggested the presence of a very large ore body, much large than the original 600 by 1500 foot claims. Graves used the money stock sales were bringing in to buy the adjoining claims and acquire the entire ore body. Encouraged by reports of other ore bodies in the district, other serious investors were moving in. In 1897 the Dominion Copper Company was formed to acquire the Idaho, Brooklyn and Stemwinder claims across the valley of Twin Creek from Graves’ developments. All of the deposits found, while large and close to the surface, were of low grade. None of them would pay for the long wagon haul to the railroad at Bossburg or Marcus.

Railroads were coming; Dan Corbin was surveying his line from Marcus to Greenwood. Fritz Heinze was surveying his route over Mc Rae Pass. The CPR was, with agonizing slowness, creeping in from Alberta. The railroads had made Rossland, and Jay Graves was confident that when one reached his mines, there would be a boom bigger than had yet been seen. A smelter would be required. To raise money for it, Graves and Aubrey White went east to enlist Montreal investors. Their pitch to the Montreallers was that it was a patriotic duty for Canadians to invest in these British Columbia mines, and not let them fall into the hands of the greedy Americans. The spectacle of a couple of Americans, Graves and White, glibly promoting Canadian patriotic sentiment was a replay of Captain Ainsworth’s arguments to the B.C. Legislature, twenty years before. Graves and White were helped by the fact that Canada was in the midst of its great Free Trade Election and the issue of American domination of Canadian business was being fought out at the polls. The anti Free Trade forces won and so did Graves. He enlisted the support of Stephen Miner, a Quebec industrialist with connections to the Montreal banking community. Miner wanted a recognized mining engineer to submit a report on Graves’ to circulate to his wealthy friends. Graves sent out another Spokane Colonel, Nelson Linsley, the head of the Spokane Mining Bureau, and a respected mining engineer, to assess the value of his claims on Knob Hill.

The report was favorable. In Montreal, Stephen Miner showed it to his friends, and introduced them to Graves who, with his tongue stuck solemnly in his cheek, warned them of the dangers of Americans getting control of this valuable Canadian resource. Might not even political annexation follow? he asked with a melodramatic shiver. Miner’s friends were impressed. The combination of patriotism plus profit was irresistible. There is something embarrassingly familiar about this to Canadians. It seems it always takes an American to arouse Canadian patriotism. With a group of wealthy Montreal investors behind him, Graves went across town to the CPR. He began lobbying the CPR directors to lay rails to his mines. The directors were skeptical. Three mountain ranges would have to be crossed, and they doubted that Grave’s low-grade copper would pay for the construction costs. Jay Graves was at an impasse. The railroad was essential to his mines. Without a firm promise of one, he and Miner could not sell stock in the Old Ironsides and Knob Hill. And until his mines demonstrated their profitability, the CPR would not move. And just as it was the threat of American control that brought the Montreal investors into Graves’ scheme, it was Dan Corbin, lobbying for a charter for a railroad to the Boundary mines, that aroused the CPR. They easily blocked his charter application in Parliament, but when Jim Hill bought Corbin’s railroad, the CPR had to act. Almost in a panic, they sent their engineers and surveyors into the Monashee snows to rush a line to the Boundary Copper camps.

The arrival of Canadian Pacific rails in Grand Forks in 1899 was marvelous luck for Jay Graves and Stephen Miner. With the CPR laying track toward their new mining camp of Phoenix, the future of their Granby Company was assured. However, Graves knew very well the CPR’s intention to create a transportation monopoly in the Boundary district, just as they had attempted in the Kootenays. And with the knowledge that only a second and competing railroad could bring the CPR ore hauling rates down to the lowest possible figure, Graves went to Jim Hill in St Paul. He showed him Colonel Linsley’s reports on the Old Ironsides and the Knob Hill. Would Mr. Hill build Dan Corbin’s line to the Boundary? Jim Hill said nothing. His game was bigger. If Grave’s ore body was as big as Colonel Linsley said, and as cheap to mine, a rail haul, while profitable, would not be enough. Jim Hill wanted the mines and the smelter as well. Very quietly, he began buying stock in Graves’ and Miner’s companies. Graves and Miner had organized three companies in 1899, the Old Ironsides, the Knob Hill, and Granby, to control the properties they owned on the ridge between Grand Forks and Greenwood. Graves brought Yolen Williams over from the California mine at Rossland, made him a director, and hired him to work out plans to extract the ore. Then, at the head waters of Twin Creek, just below their claims, Graves and Miner preempted a town site, called it Phoenix, built a water system, and began selling lots to merchants, saloon keepers, hotel men, and others moving to the new camp. The town site was a huge success. Buyers flocked in, scenting a new Rossland. Within 24 hours of going on sale, nearly every lot was sold for between $500 to $600. It was said that the town site sale brought in $100,000 to Granby. Graves and Miner now had enough for a down payment on a smelter, and began to build one on the North Fork of the Kettle River, just over Observation Mountain from Grand Forks. Breathlessly, miners, businessmen and investors, watched the CPR’s branch line to Phoenix being graded around the eastern slopes of Deadman’s Hill toward the mines. With the CPR laying tracks to their ore, and with directors, Miner and Gault, handling stock sales in Montreal, Aubrey White moved to New York and began selling shares there. They began moving briskly in the range of 80 cents. This was delightful news to the Spokane speculators who had bought their shares for a nickel. And at 80 cents, Jay Graves was now a rich man.

The Guggenheim brothers at that time dominated American metal smelting and refining. Walter Aldrige at Trail had served in one of their Colorado operations. Now Graves hired another one of Guggenheim’s smelter engineers, Abel Hodges, to put up a first class smelter on the North Fork site. With all this activity, the CPR queried Walter Aldridge, whether the Phoenix development was serious. Aldridge, who badly wanted the Phoenix ores for his Trail smelter, told President Shaughnessy that it was quite serious, and that the Old Ironsides held enough ore to support a small smelter. Shaughnessy was asked by Graves to build a 2-mile CPR spur into the smelter site from the C&W main line at Ward Lake. It was needed as quickly as possible, Graves emphasized, as the smelter machinery to be installed would be much too heavy for freight wagons. Aldridge and Shaughnessy wanted the Phoenix ore for the Trail smelter, and were in no mood to facilitate a competing smelter. They told Graves Granby would have to pay for the smelter spur itself, but the cost would be refunded if the smelter production should reach 100 tons per day. Aldridge underestimated Granby. The Phoenix ores were lean, averaging only 1-1/4 percent copper, and would require several smeltings to concentrate them enough for refining. Abel Hodges assured Jay Graves that he could smelt 150 tons of Phoenix ore a day, and that the spur cost would be recovered.

The CPR’s Phoenix branch left the main line at the Eholt summit and climbed up Coltern Creek on a 3.4 percent grade. At the head of the creek a small side hill cut, exposed a mass of chalcopyrite, a sulfide of copper and iron. An alert workman quickly drove stakes on it and sold it to the Dominion Copper Company as the Emma Mine. Aldridge and Shaughnessy were in no hurry to serve Jay Graves’ interest, and at this spot they abandoned the climb to Phoenix and ran a 2-1/2 mile spur out to the B.C. mine. Aldridge urgently wanted that mine’s ore, almost pure copper pyrites, for his Trail smelter, as its high sulfur content would only require enough coal to ignite it in the smelter furnace. From then on the burning sulfur itself would smelt the ore. Graves was furious. The CPR was hauling Boundary ore to Trail before putting rails into his deposit. If Jim Hill were only on the scene, the CPR would not be trifling with him in this way. Angrily, he had to send his first ore shipments down the mountain by wagon to the Granby Smelter for its opening on April 11, 1900, exactly as the Le Roi had had to do from Rossland, four years previously. Finally, the CPR sent its crews back to the Emma mine, and began grading up the east side of Deadman’s Ridge toward Phoenix. Not a quarter mile from the Emma, their grading exposed another mass of copper ore, and with no Trail engineer present, it was staked as the Oro Denoro, and sold to the Dominion Copper Company.

From that point the graders carefully examined every stone for traces of copper, but no further bonanzas were uncovered in the steep climb to the ridge top flat at the Wellington Camp (later Hartford). At the chaotic Wellington Camp the ground was covered with stores, tents and cabins whose owners demanded exorbitant prices for a right of way. The CPR hastily put in a switchback on perfectly level ground rather than pay for the land needed for a loop. (Later on, when the Wellington Camp declined, a loop was built.) The switchback reversed the line north where it climbed through the Rawhide, Gold Drop, Curlew, and Snowshoe claims, and turned into a shallow pass at an elevation of 4500 feet to enter the head waters of Twin Creek, the new town of Phoenix and the Granby Company’s mines.

In June of 1900, the rails were spiked down, and the line was complete. On July 11, the first trainload of ten 30-ton cars of ore from the Old Ironsides mine departed Phoenix behind CPR L class Consolidation No. 317. At Smelter Junction, the train was split, with five cars set off to be forwarded to the Trail smelter, while the remaining five cars were trundled down the 2 mile spur to the to the Granby Smelter. They arrived at 5:30 PM and were received with elaborate ceremony. Jay Graves and his family, together with C.H.S. Miner, Abel Hodges, and their families, were present. A local brass band played, and the whistle cords of the engines were tied down to express the jubilation of all present. It had been a tremendous gamble, but Jay Graves had won. The two smelter furnaces were fired up the next day, and another trainload of ore arrived, the beginning of daily shipments from Granby and the other mines in the region. Jay Graves at once ordered two Thew steam shovels on flanged wheels for 36” gauge track. Quarry faces were blasted into the ore bodies at the Old Ironsides and the Knob Hill, 36” track was laid, and the two shovels began digging out the broken ore and loading it into 4 ton mine cars. Davenport 0-4-0 saddletanker locomotives hauled the mine cars out of the quarries to a loading platform where they were dumped into the CPR 30 ton ore gondolas below. At least one of the Davenport saddletankers was a special model for underground use, cut down to a five foot height, and requiring its engineer to operate it and fire it from a sitting position. This squat steamer could enter the caverns blasted into the quarry walls and pull out ore from underground.

All this mechanization was wonderfully efficient. Jay Graves boasted accurately to reporters that the Granby ores moved from quarry to smelter untouched by human hands. Dumping the mine cars was mechanized a few years later when a Granby employee invented the self-dumping Granby mine car. A wheel on the outside of the car would ride up on a slanting rail fixed to a vertical bulkhead in the dumping shed and tip the car as the Davenport pushed it over the chute. This “Granby Car” was sold all over North America in subsequent years. As soon as the CPR tracks reached the mines at Phoenix, production went on a six-day week. The ores rolled in short trains down the steep 12 mile grade to Eholt where they were made up into trains for the Granby smelter and cuts of cars for Trail to be picked up by the next way freight. A second Shay locomotive, No. 112, identical to the 111 working the Rossland hill, was ordered and put to work on the Phoenix line hauling ore down the hill, and bringing coal and freight up to Phoenix.

With the completion of the Phoenix line, the CPR shifted its crews to Greenwood to build another steep and crooked branch up Motherlode creek to serve the Deadwood, Sunset and Motherlode mines. The branch left the main line just a few hundred feet north of the C&W station, and climbed the rock bluff above Boundary Creek on a 3.8 percent grade to enter Motherlode Creek above the new smelter being built by the B.C. Copper Company. From the smelter, the line climbed the left bank of Motherlode Creek to the town of Deadwood, and the Greyhound and Deadwood mines, also open quarries like the Phoenix mines. From Deadwood the line was built on that same 3.8 percent grade up Castle Creek to a switchback (later replaced with a loop) which reversed it out of Castle Creek and up Motherlode Creek again to the huge Sunset open pit, or “glory hole,” as they were then called. A quarter mile farther on it reached the Mother lode mine and its even bigger glory hole. Shay 113 was purchased in 1903 to work this branch.

The CPR surveyors had continued past the Motherlode mine, locating a line winding in and out of creek valleys and looping around the noses of ridges to Dan Corbin’s King Solomon mine. This location was known as Copper Camp, at 4400 feet elevation, with the King Solomon and Enterprise as the major producing mines. The line past Motherlode, however, was never graded or built. Probably because the CPR demanded the mine owners pay for it, with reimbursement after a certain tonnage had been shipped. Agreement was evidently never reached, and the end of track remained at Motherlode with the King Solomon and Enterprise ores coming down to that point on wagons.

From the Canadian Pacific’s point of view, the building of the Columbia and Western with its spurs and branches was more a defense against Jim Hill than a profitable investment. They had spent an estimated 7 million dollars to put rails into the Boundary country from Robson West, and yet the mining companies had spent but 4 millions in their developments. Worse, the startling news came that Jim Hill had bought the supposedly defunct charter of the Vancouver, Victoria and Eastern and his surveyors were staking grades into the Boundary country and up into Phoenix itself.

The CPR built a further spur from the Eholt-Phoenix line to serve the Jackpot and Athelstan mines, and surveyed two more grades long the spine of the Midway range across the border to reach the City of Paris and No. 7 mines at White’s Camp, and the Washington and Lone Star at the head of Big Goosmus Creek in Washington.These two last branches were never built; again, the owners would not pay, and found they could build a 5-mile aerial cableway to transport their ore back across the border into Canada and down to a second Boundary Creek smelter being erected by the Dominion Copper Company. It went into operation in 1901. With three smelters competing against him for Boundary copper, Walter Aldridge was finding it difficult to obtain sufficient ore for his Trail smelter. His Canadian Mining and Smelting Company was obliged to buy or lease producing mines to secure a dependable supply of smelter feed.

By 1902 the Granby smelter was operating at capacity, and still more ore was coming down from the huge Knob Hill and Old Ironsides pits. Graves and Miner merged all their Companies into Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting and Power Company, Ltd. and issued $15 million in stock. $11 million went to the stockholders in the old syndicate; the rest was put on the market to raise funds for enlargement of the smelter, the installation of a converter to produce nearly pure copper, and for a hydroelectric plant at Cascade, on the Kettle River, to furnish additional power for the smelter and to electrify the mines at Phoenix. This enormous capitalization looked suspicious to many. No one knew how deep the Old Ironsides and Knob Hill ore bodies were. Did they really have $15 million dollars worth of ore? Neither Graves nor Miner could answer this question definitively. Speculators wondered if Graves and Miner were preparing to sell out at this inflated value before the ore bottomed out.

For his part, Graves had a new scheme. This minor real estate developer from Spokane was going to try to play the two hostile railroad barons against each other for his own interests. Graves was never shy; he approached Thomas Shaughnessy, President of the CPR, with a plan to keep Jim Hill out of Phoenix. He proposed that Granby should continue to smelt its own ores in its own smelter. But since there was more ore now coming out of the ground on the heights around Phoenix than the Granby smelter could handle, and the cost of transporting ores to Trail over McRae pass was uneconomic, the CPR could build a second Grand Forks smelter, a custom smelter to handle all the ores from the mines not owned by Granby, B.C. Copper, or Dominion. These ores could not stand the shipping charges to Trail and were going begging for treatment. If the CPR would build this custom smelter, Graves promised he would offer as security for loans to build it, 28 options he held on mines in both the Phoenix area and also down in Republic, Washington in the new Eureka Creek mines. If the CPR accepted his offer, he would guarantee them the haul from all these mines to the custom smelter as well as the Granby haul to its smelter. Graves estimated revenue from these hauls to be $800,000 per year. It was not unreasonable; CPR was already getting $380,000 a year from its haul to the Granby smelter alone. It was a clever scheme; by using the capacity of a second Grand Forks smelter to contract for all the Boundary ores offered, nothing at all would be left for Jim Hill to haul. He might run his rails up to Phoenix if he wished, but when he got them there, there would be nothing to load into his cars.

If the impetuous Van Horne had still been in charge, he might well have agreed. But the cautious, conservative Shaugnessy was now President. He sought advice from Walter Aldridge. Aldridge told him the Boundary mines were overrated, that they were shallow deposits that would soon play out, that Graves could not demonstrate proven reserves of ore. Shaugnessy turned down Graves’ offer. As it turned out, this was a spectacular mistake. Copper prices would soar during World War I making even the poorest Phoenix ores profitable.

Undismayed, Graves turned around and sounded out Jim Hill. His new scheme, which he put to Hill, was nothing less than a proposal that the two of them should buy Granby outright. He asked Jim Hill for a loan of $2 million to buy 500,000 shares of Granby at $4. With the 150,000 shares he owned or controlled through relatives and employees that would give Hill and himself control. With control of Granby, Hill, when his rails reached Phoenix, could then take all of the Granby traffic and the CPR would be starved of ore. After promising funds, Hill had second thoughts. His suspicious nature which George Stephen had played upon so successfully, asserted itself. He could not bring himself to participate in another man’s scheme. When Graves got to Montreal to make his stock purchases, there was no money waiting for him. He found the Granby directors ready to sell, as he had predicted to Hill. They thought the future for copper was speculative, and wanted to get out while the stock price was favorable. They were selling, however, to William H. Nichols, a New York copper refiner. Frantic letters to Hill produced no result. Graves’ scheme was slipping away from him. When the other directors, unaware of Graves’ intentions, invited him to go along with them and sell to Nichols, he had to agree. Hill eventually sent him a stingy $25,000 in New York in case Nichols should change his mind, but it was too late. Nichols and his New York associates had bought Granby outright.

One has to wonder at the eagerness of the Canadian stockholders to sell out to the Americans when it had been appeals to their patriotism that had brought them into Granby in the first place. Emotionalism is probably much more a factor in business than most will admit. In 1902 Jim Hill’s men crossed the border into Canada at Cascade and began grading toward Grand Forks. There they were halted by an injunction obtained from the court by one of the most preposterous railroads ever to run a train, Tracy Holland’s “Hot Air Line.” Jim Hill had encountered his newest and most pestiferous adversary.