Microscopic Note Writing

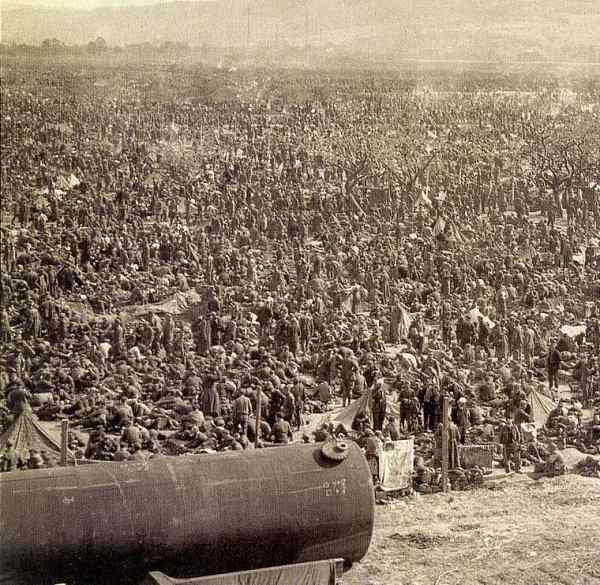

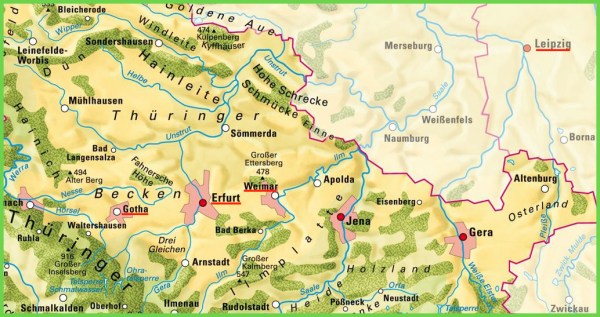

Finally, on May 7, the weather showed signs of improvement, and on the following day, the sun broke through the cloud cover, bringing much-needed warmth for body and soul. However, Papa’s feet and toes were numb; he felt a tingling sensation throughout his lower limbs and could barely walk. His heart began to give him trouble. He knew that he would not have lasted much longer. But now, as he was feeling better and his feet were no longer bothering him and after he was finally able to clear himself of all the dirt on his body, wash his shirt and socks, a sense of new optimism was surging through his entire being. Rumours were also circulating through the camp that the POWs would get permission to go home. The war was over now. Why would the Americans want to keep them any longer? Would it not be cheaper to make them go home and save the expense of looking after, feeding and guarding 80,000 men? But just as Papa was looking in vain for blue patches in the leaden sky, so all his hopes for early dismissal vanished into thin air. Camp life went on with its daily routines. The camp guards became rather more severe as days dragged into weeks and weeks into months. They meted out ruthless punishments after some POWs in constant search for firewood had ripped off some of the toilet seats from the camp latrines.

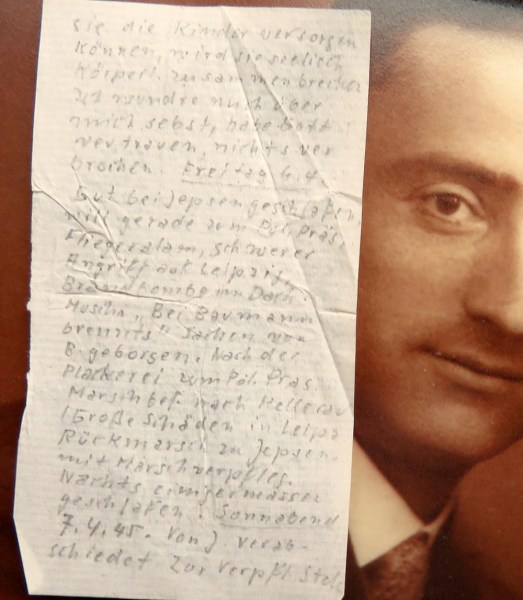

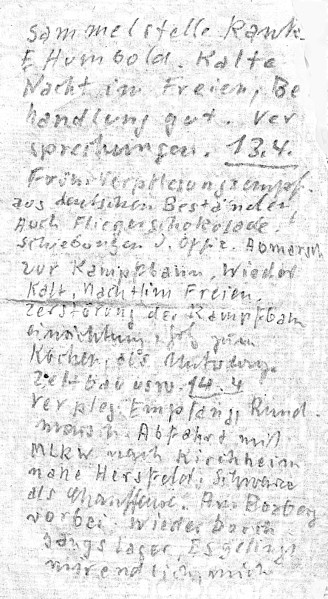

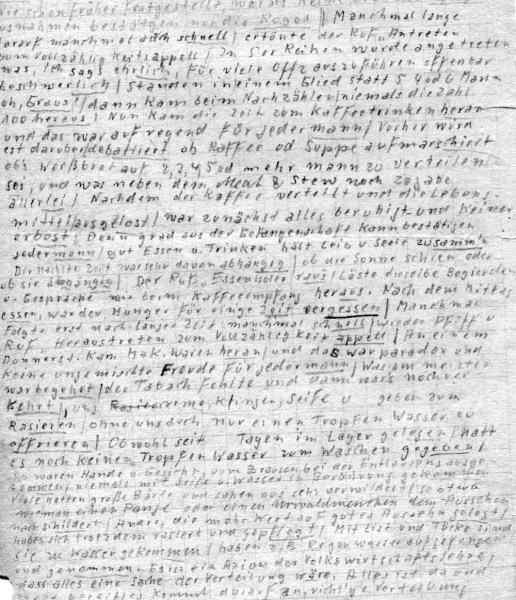

Papa was not the type who would not want to idle away the time by just sitting around in the sunshine or play cards for endless hours, even if it was his favourite card game, ‘Skat’. He wrote his notes now on slightly larger paper but continued with the same microcosmic handwriting. Of course, Papa knew that it was strictly forbidden to record his experiences at the camp and therefore was extremely careful not to let anyone see him write. I guess the reason for these rules was that nothing should ever go out to the outside world that might tarnish the image of the Americans.