THE WILD HORSE RUSH

THE WILD HORSE RUSH

The Two Boundary Commissions, British and American, arrived on the Columbia in 1860, to build their barracks, the Americans at Pinckney City next to the U.S. Army camp, the British just north of the HBC post at Fort Colvile on the Columbia. Sections of boundary were assigned alternately to British and American surveying crews, and in 1861 they went to work.

The British Boundary Surveyors were the first to report finding gold. When they returned to their barracks in the fall of 1862 they brought specimens of gold in quartz which they had obtained from from the upper Kootenay River Indians. Once again, it was the Aboriginals who produced the gold for the Europeans to “discover.”

When these samples were displayed in Colville, the prospector’s hotels emptied into the streets at once. A throng of wildly excited men demanded information.The gold was examined, the surveyors repeatedly questioned as to where it had been found. Partnerships were instantly formed, parties organized to exploit the new strike in the spring. Prospectors sought grubstakes from local merchants, a grant of supplies for the coming season, with the merchant to receive half of what might be found. The larger parties were organized with a leader and regulations as to what size of claim was to be allowed, the days of work (Sunday was universally established as a day of rest), and the duties of each member on the trail and at the diggings. Merchants sent off orders for provisions and supplies to come up from Portland by boat to White Bluffs (opposite the present Hanford Nuclear Site) and from there up the wagon road to Colville. The town took on a look of excited prosperity, all based on what the miners hoped to find the next summer.

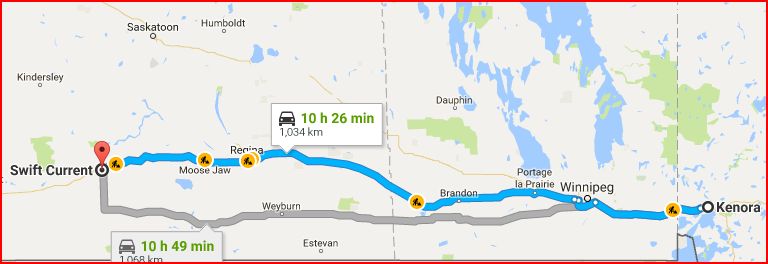

When the snows melted off the mountains in April of 1863, Robert. L. Dore led the first party out of Colville up the wagon road to Pend Oreille where an old HBC trail led north. Five hundred men, from Colville and from Walla Walla, were on the trails that spring, and the Wild Horse rush was on. The route was across the open grasslands to Pend Orielle Lake. From there the miners went up the Pack River, crossed the low divide to the Kootenay River where rafts or crude boats had to be made to effect a crossing. One of the men, Edwin L. Bonner, bought a piece of land at the crossing from Chief Abraham, established Bonner’s Ferry, and settled down to collect tolls.

Once across the Kootenay the trail crossed Serviceberry Hill to the Moyie River, and over the height of land to Joseph Prairie (present Cranbrook). From there open grasslands led down to the Upper Kootenay River where John Galbraith saw his chance and built a ferry to carry miners across. Wild Horse Creek was a few miles farther on, up river.

It should not be thought that all on the trails were miners. Many were merchants who were veterans of other rushes and had seen what extraordinary prices provisions could command in an isolated mining camp. Daniel Drumheller tells of his trek to Wild Horse.

“…we were receiving flattering reports of the rich placer discoveries on Wild Horse Creek in the East Kootenays of British Columbia. I bought a half interest in a pack train from Charley Allenberg… we bought our goods, packed our animals and started for Wild Horse Creek…. When we reached the Kootenay River… I met E.L. Bonner, R.A. Eddy, Dick Rackett, and John Walton, all old friends of mine… when they reached the Kootenay River they saw a chance to make some money by building a ferry boat. They had a whip saw with them and were engaged in sawing lumber to build the boat… Bonner and Eddy both accumulated large fortunes.

“We finally reached our destination, Wild Horse Creek, B.C., June 15, 1864… and found about 1,500 miners already on the ground,and about 200 straggling miners arriving daily. We built a little shack of logs a few rounds high and covered it with canvas and then opened up a little store. My partner, Charlie Allenberg, was more merchant than packer, so he took charge of the store. I sold out little pack train and then devoted myself to prospecting and mining.

“When I was ready to go prospecting I met an old California placer miner by the name of Steve Babcock. I asked Mr. Babcock what he thought of the camp. He said he had done some prospecting, but found nothing, and believed the diggings were going to prove quite limited. The camp was on the widest part of a high flat or bar. This bar as about one mile in length and its widest place was 300 yards. The creek running along this side of the bar was the richest ground in camp.

“One morning Babcock and I took our mining tools and what grub we could pack on our backs and started to go out about six miles to prospect a stream called Stony creek. We had only proceeded a hundred yards when we stopped to arrange our packs. We were then near the upper end of the bar on which the camp was built. When we had our packs arranged, I said to Bab:

“’I’m a poor packhorse and why not prospect this bar before going further.’

“Bab consented and said he had several times in mind to sink a hole in this bar. Without further ceremony we went to work. The bar at this point was perhaps 330 feet wide. We put down five prospect holes to bedrock across this bar about 50 feet apart. It was from four to six feet to bedrock. We found but very little gravel in any of our prospect holes even on the bedrock and no gold.

“The bedrock was of slate formation, craggy and checkered with deep seams. Neither Bob nor I had any experience of mining on that kind of bedrock. After finishing our fifth hole we went out and prospected Stony Creek, but found no gold. We were gone about 10 days, and on returning to camp, when we came in sight of our five prospect holes, hundreds of men were standing around then. I said to Babcock that very likely some drunk had fallen into one of our prospect holes and broken his neck. When we approached these men I asked one of them I know what was causing all the excitement. He said:

“”Haven’t you heard the news?”’ I said, ‘No.’ When this man was able to speak again he said:

“”This morning Jobe Harvey, the barkeeper, was looking down into one of your old prospect holes and saw something glittering in a deep crevice in the bedrock. When he got it out it proved to be a nugget of gold weighing $56.’

“We were too late to secure a location. This bar produced more gold than all the balance of the camp.”

On arriving, the Colville prospectors fanned out, checking all the creeks in the vicinity. They found they were not the first on the ground. A party of lawless Montana men were already present. They had come in via the trail from Flathead Lake and the Tobacco Plains. Many of these were violent men who had been ordered out of Montana by the various “Vigilance Committees.” While they had been wintering at Frenchtown, near present Missoula, a mixed breed Indian from the Findlay band in the East Kootenay came to visit the French settlement. With him he had some gold nuggets he said he had picked up out of seams in the bedrock in a small stream flowing into the Kootenay River 40 miles above present Fort Steele.

The prospectors hired this Indian to lead them to the place, leaving Frenchtown the First of March. When the men reached Wild Horse Creek they left their exhausted horses with three of their men, Pat Moran, Mike Brennan and Jim Reynolds. The rest walked upriver to Findlay Creek but found little gold. In their absence, the three men left behind with the stock began prospecting on the open sections of Wild Horse creek. Four miles upstream in a box canyon they struck rich ground. At once they held a miner’s meeting and drew up laws to govern size of claims and the means to hold them. “Uncle Dan Drumheller,” tells what happened next,

“There had been a great feud existing between the miners from the east of the Rockies and those from the west… and there was a free-for-all fight in a saloon. One man, Tommy Waker, was killed. Overland Bob was hit over the head with a big hand spike and a fellow by the name of Kelly was stabbed with a knife in the back. “A mob was quickly raised by the friends of Tommy Walker for the purpose of hanging Overland Bob and East Powder Bill. Then a law and order organization numbering about 1000 miners, of which I was a member, assembled. It was the purpose of our organization to order a miners’ court and give all concerned a fair (hearing). The next morning we appointed a lawyer by the name of A. J. Gregory as trial judge and John Mc Clellan sheriff, with authority to appoint as many deputies as he wished. That was the condition of things when Judge Haynes, the British Columbia (Gold) commissioner, rode into camp.

“’Fifteen hundred men under arms in the queen’s dominion. A dastardly usurpation of authority, don’t cher know,’ remarked Judge Haynes. But that one little English constable with knee breeches, red cap, cane in his hand, riding a jockey (English) saddle and mounted on a bob-tailed horse, quelled that mob in 15 minutes.”

This “English constable” was John Carmichael Haynes, rancher at Lake Osoyoos, appointed Gold Commissioner for southern British Columbia and sent 300 miles east via a long detour into Washington territory to Wild Horse to issue miners’ licences, register claims, collect duties and the gold export tax. In his report to the Governor he confirmed a thousand men on Wild Horse and Findlay Creeks. As “Uncle Dan” reported, they had drawn up the mining laws of the district to regulate the work and avoid disputes. These were accepted by Haynes and enforced by his constable. But however cooperative the miners were in matters of mining and criminal law, they were extremely reticent about the amount of their takings, since they wished to evade, if possible, the export tax on gold. Governor Douglas had imposed a tax of 50 cents per ounce on exporting gold in a vain effort to compel the miners to sell their dust and nuggets to the HBC post at Tobacco Plains for forwarding to New Westminster.

Again as had happened on the Fraser, the miners, in absence of local authority, drew up their own laws and appointed their own officials. But once a self-assured representative of Colonial authority manifested himself and demonstrated probity, and ability to keep the peace, the Americans were quite willing to accept his rule. Except, of course, in that matter of the “un-American” gold export tax. On that, the Magistrates and Gold Commissioners had to accept the pragmatic dictum that only those laws can be enforced, which the citizens are willing to have enforced.

In the fall all but a few of the men headed back down the trails to the Washington Territory to share their take with the merchants who had grub staked them, pay their hotel bills, and find a warm room for the winter. For the few that stayed on the placer grounds, the winter was trying. Flour cost $2.50 per pound, tobacco was $15, and opium, quite legal, and the widely used remedy for “cabin fever,” went for $12 an ounce, nearly as much as gold. The two supply trails, one to Colville, the other running southeast across the Tobacco Plains into Montana and east to Fort Benton, the head of navigation on the Missouri River, were open during good weather in the winter as the dryer Rocky Mountain Trench was spared the deep and impassible snowfalls of the Columbia and Kootenay Lake districts. By the end of May supplies were being packed in at $.28 per pound. As well, the previous year’s miners were returning to take up their claims and locate new ones.

Good locations the summer of 1864 were paying $60 per day. With the news out and pack trains coming in from both Montana and Colville, food was plentiful. Haynes, named Magistrate in 1864, through his constable, issued twenty-two traders’ licences, twelve liquor licences,and over six-hundred miners’ licences. In the month of August alone, the revenues amounted to over $11,000, of which more than half was customs duties. By fall, a sawmill had been packed in pieces and assembled to saw flume and cabin lumber. Several sluice companies had dug ditches, and built flumes to bring the water to the best locations. These companies, with five to twenty-five men, each, were taking out from $300 to $1000 per day. The gold was remarkably pure, going for $18 per ounce. A town called Fisherville had spring up, then had to be moved the next year, as gold was discovered underneath it.

The Colonial Secretary, A. N. Birch was sent (via Washington Territory) by Governor Douglas to investigate. On his return he carried the Government receipts, seventy-five pounds of gold, to New Westminster.

More miners stayed over the second winter, but the food situation again became difficult. The B.C. constable stationed there wrote Judge Haynes at Osoyoos on Dec. 1,

“Provisions are becoming scarce already. Flour is $65 per hundred pounds, and little left.”

The winter of 1864 – ‘65 was severe, and the remote camp at Wild Horse was not prepared for it. The Colonial official wrote,

“There are no more than 300 men remaining here. I yesterday recorded 12 claims on a creek called “Canyon, ” about 200 (miles) from here. Many have returned after much hardship, not one of whom succeeded in reaching the new diggings.”

By spring the situation was serious. The constable wrote on April 1,

“The winter is one of unusual length and severity. Mr. Linklater of the Hudson’s Bay Company reports more snow than for twelve years previously in residence at Tobacco Plains. Upwards of 200 head of cattle have perished there and many packers have lost their trains. We now have 500 men in camp. No breaches of the peace. Mr. Waldron reports that of two men starting before him (on the Walla Walla trail) one died from frost-bite, and the other will probably lose his legs. Money is scarce; provisions scarcer. In another week, not a pound of food can be purchased at any price; $100 would not purchase a sack of flour today. The last flour sold at $1 per lb. All that is left is a little bacon at $1.25 a pound. Some twenty pounds of H.B. rope tobacco brought in today was sold in twenty minutes at $12 per pound, a hundred more would fetch the same.”

At these prices merchants were eager to get in a pack train of supplies and set up a log store. The profits to be made from a mining camp exceeded any other sort of enterprise and no digging was involved. It was especially galling for Victoria and New Westminster merchants to read these reports from the Kootenay country where men desperate for provisions were being supplied entirely and at huge profit from the Montana and Washington Territories.

A few weeks after the above report, the first miners of the new season arrived. The Wild Horse official wrote Commissioner Haynes,

“Four men from Flathead Lake (Montana) arriving yesterday tell me of a train of goods there waiting to get in. The goods were brought from Fort Benton on the Missouri to Flathead. If they do not arrive, and with beef cattle, in the promised twelve or fourteen days… we shall suffer semi-starvation. Many are now reduced to bacon and beans without flour, and not a few are without food of any kind.”

It may be wondered, that these hardy men in the midst of a country, plentiful in game and fish, should face starvation. This was typical of all the gold camps. In their obsession with gold, miners gave every waking hour to pick, shovel and pan, washing out the gold. When creeks froze in winter, they would be out whipsawing lumber to construct flumes to bring the runoff water in the spring to their claims to flush the gold bearing gravels into their sluices. Miners were not “mountain men,” living off the country. Almost all of them were townsmen, accustomed, winter and summer, to living off purchased provisions. Fish and game they would buy from the Indians when they brought them to the camps, but sparing time to grow a garden or to hunt or fish, while their fellows might get a lead on them in digging the bars, was unthinkable. The miner with lard buckets full of gold dust and nuggets under his bed, considered himself a rich man, purchasing his provisions, and scorned those who produced them. It was the madness of greed, and was repeated in every gold camp in the West.

The cool heads, of course, observed all this, took note of the fact that while a few miners came out in the Fall rich, most, like Uncle Dan Drumheller, lost money on their prospecting expedition, spending every ounce of gold they panned on costly provisions. A merchant with a pack train of supplies and particularly liquor, could not lose money in a gold rush; most prospective miners did.

In 1865, with the Cariboo District on the decline, Gold Commissioner O’Reilly was sent to Wild Horse instead of Barkerville. Fisherville became a town of 120 houses and some 1500 to 2000 men were in the district. The Victoria Ditch was completed at cost of $125,000 to bring water to 100 dry claims, and shafts were being sunk through the gravel as much a 80 feet to reach the bedrock where the gold lay.

1865 was the banner year for Wild Horse. Government revenues reached $75,000. The New Westminster Government under its new Governor Seymour, prodded by the merchants who wanted to get in on the trade, sent out two parties to locate an all-British route to Wild Horse. One party, led by George Turner, former Royal Engineer, started from Kamloops, and went up the South Thompson River to Shuswap Lake. They then took the old HBC trail from Seymour Arm to Death Rapids, just below the Big Bend of the Columbia River. The intention was to brush out the old HBC trail up the Columbia past Windermere Lake and down the Kootenay to Wild Horse. However, the party ran out supplies at Big Bend and had to turn back, noting that local Indians were finding a little gold near the mouth of the Canoe River.

The other party had better luck. Led by J. J. Jenkins, they took the Dewdney Trail from Hope to Similkameen, visited Judge Haynes at his Osoyoos Ranch, climbed Anarchist Mountain and descended to the now largely deserted diggings at Rock Creek. Almost all of its miners had moved on, either to the Cariboo or Wild Horse. Jenkins and his men pushed on over the Boundary Range, down into the Kettle River Valley, past Christina Lake and over the Rossland Range to the Columbia at Fort Shepherd. Their route tip-toed just north of the border, in many places using the swathes cleared through the timber by the Boundary Surveys. From Fort Shepherd, they crossed the Columbia, ascended Beaver Creek and crossed the high Kootenay Pass to the Kootenay River Flats. The river came across the border from the U.S., so they were obliged to climb the mountains again and cross to the Moyie River where they struck the miner’s Colville – Wild Horse trail.

Jenkin’s route was adopted by Governor Seymour, and money was appropriated to have Edgar Dewdney extend his Hope to Osoyoos trail to Wild Horse, four feet wide and 400 miles long. But as a counter to the American routes, this extended Dewdney Trail was a laborious grind. Climbing the Cascades out of Hope it crossed Hope Pass at an elevation of 5900 feet.(1799 meters). Obliged to stay north of the border, the trail crossed the Okanagan Range at 4000 feet ( 1220 meters), the Boundary Range at 4200 feet (1281 meters), the Rossland Range at 5300 feet (1616 meters), and the Kootenay Pass over the Bonnington Range at 6000 feet (1830 meters). This meant that the trail was closed by snow most of the year, really only usable from July through October. American trails, running up the river valleys from the Washington Territory crossed nothing higher than the gentle 3400 foot (1037 meter) height of land between Moyie Lake and Joseph’s Prairie. This gave the American pack trains an 8 month’s season as against a four month’s season on the Dewdney Trail. On the Dewdney trail from Fort Shepherd to Wild Horse one of the the HBC pack trains was 14 days on the trail and lost six horses on the way. Its use was practically limited to HBC supply trains for the Tobacco Plains post and the comings and goings of Colonial Officers. The Americans had the river crossings on the Colville and Walla Walla trails covered by ferries. None existed on the Similkameen, Okanagan, Kettle, Columbia or Lower Kootenay on the British route. To cross, an Indian had to be found and his canoe hired. The Dewdney trail did, in a laborious fashion, link New Westminster to the Columbia and Kootenay regions, but it is doubtful that any but a few Magistrates and Constables ever took it twice. And the Kootenays, as before wide open to the American merchants, remained connected to the Coast, the government, and the British commercial establishments only by a 400 mile horse trail.

In a vain effort to keep miners supplies and provisions from coming in via the Washington and Montana trails, the Colonial Government sent in Constables to collect the customs duties and gold export tax. At Osoyoos, Magistrate Haynes, a local rancher, had two constables and a collector of customs to intercept pack trains on the old HBC trail from Fort Okanogan. At Fort Shepherd on the Columbia, one constable was stationed. At Rykerts, on the Kootenay River north of Bonner’s Ferry, one constable. At Wild Horse, a magistrate, two constables and a collector. At Galbraith’s ferry, on the Colville/Walla Wall trail, one constable. At Tobacco Plains, watching the Montana trail, one constable. These twelve men were expected to guard and area the size of Ohio, plus 300 miles of border. Remarkably, they did, keeping order and collecting at least some of the duties as required. A letter to the Colonial Secretary praises their vigilance, but of course, that is what they wished their superiors to hear.

“In fact it is almost impossible to evade duties, as there are but three trails by which goods can be imported (to Wild Horse) — one by Tobacco Plains, one by the junction on the Moyie, and one from Colville to Fort Shepherd, all of which converge about twenty miles from the mines. The long, low stretches of land on the Kootenay, flooded during the summer months, and the unbridged and unfordable Kettle, Goat and Salmon (Salmo) Rivers render the (Dewdney) trail almost impassible, and travelers and pack trains are obliged to make a detour of 160 miles through American territory, by Colville, Spokane Prairie and the Pend d’Orielle (sic), meeting the Fort Shepherd (Dewdney) trail at the Junction on the Moyie River, about sixty miles from the mines. Until this detour is made unnecessary, colonial merchants, on account of the increased pack distance charges and the American bond system, cannot establish mine branches (stores at the mines) and compete with Walla Walla. These obstacles prevent the unfortunate people here from having any regular mail system. There is no communication of any kind in winter, and even in summer they receive an Express but four times.

There were urgings to the Colonial Government to attempt to keep the Dewdney Trail open in winter, at least from Hope to Osoyoos. Post houses were recommended every ten miles, to shelter the traveler and his animals. However, the Colony had assumed a crushing debt in building the Cariboo Road, and had no wish to spend money on another rush which might prove short-lived. The Dewdney Trail remained a fair weather route, and dubious even then. Judge Haynes wrote from Fort Shepherd on May 3, 1866,

“The trail between this place and Kootenay (Wild Horse) is, owing to snow, impassible for animals and by all accounts it will, in its present unfinished state, be more so by high water. Dewdney’s Trail; between this and Boundary Creek (the section from Rock Creak to the Columbia) is as yet impassible owing to snow.”

Notwithstanding the presence of some 5,000 armed miners, rabid with gold fever, all reports attest to the lawful behaviour of the men once a magistrate and his two constables were sent in. To the south, Montana was in the throes of vigilante justice, with murders and extralegal executions frequent. The Buffalo Hump camps in Idaho were unruly and murderous, and only the Army, it seemed, was keeping the peace in eastern Washington. Still, when Colonial Secretary A. N. Birch arrived on tour of inspection in 1864 he found,

“…the mining laws of the Colony in full force, all customs duties paid, no pistols to be seen, and everything quiet and orderly.”

Magistrate O’Reilly in 1865 was obliged to arrest three Americans for bringing in and circulating counterfeit gold dust, but he reported in his summary for the year,

“It is gratifying to be able to state that not an instance of serious crime occurred during the past season, and this is perhaps the more remarkable if we take into consideration the class of men usually attracted to new gold fields and the close proximity if the Southern Boundary, affording at all times great facilities for escape from justice.”

O’Reilly did, however, admit in his report that he had received but $6,900 in export duties on gold, which he suggested represented but a fifth of the gold actually taken out. The conclusion is, that although the Americans were perfectly willing to submit to a fair and incorruptible administration of the criminal law by men they respected, they reserved to themselves the right to evade laws which had no counterpart in the U.S. The American placer miners on the Columbia, the Thompson, the Fraser, and the Wild Horse, were willing to have the criminal laws and their own mining regulations enforced by British authority, but when it came to a charge on their gold, a relict of that ancient “Quinto,” they, like the Mexicans, probably like miners worldwide, would evade it if they possibly could.

At Wild Horse a final irony was to come. As the Indian labourers under foreman William Fernie, were completed the final section of the extended Dewdney Trail from Joseph’s Prairie to Wild Horse in 1865, they found an almost deserted camp. The Wild Horse miners had decamped to a new bonanza. The Big Bend Rush was on. The Dewdney Trail, a hopeful artery of commerce on paper, had been an utter failure on the ground.