CHAPTER SIXTEEN

SLOW DEATH:THE DEMISE OF THE HOT AIR LINE 1902 – 1921

After the arrival of the W&GN rails in Republic in 1903, the production of the mines was split between the two railroads. Approximately 1000 tons per week was going out, with the GN taking the largest share. Most of this ore had been stockpiled at the mines awaiting the rails. Almost all of the 30 carloads a week being shipped, went to the Granby smelter. Very high grade ores went to Everett and Tacoma, Washington where the smelters were willing to pay premium prices for Republic ores with their high silica and lime content, to blend with their “wet” (high in sulfur) ores to make a desirable slag in the furnaces.

Once the stockpiles of ore had been shipped, traffic began to dwindle from 35,000 tons with a value of $350,000 in 1903 to a mere 195 tons with a value of $9,000 in the panic year of 1907. It was not an indication that the mines were exhausted. Recovery of the gold values was the problem, not exhaustion of the deposits. When better concentrating methods were installed in the larger mines, production increased.

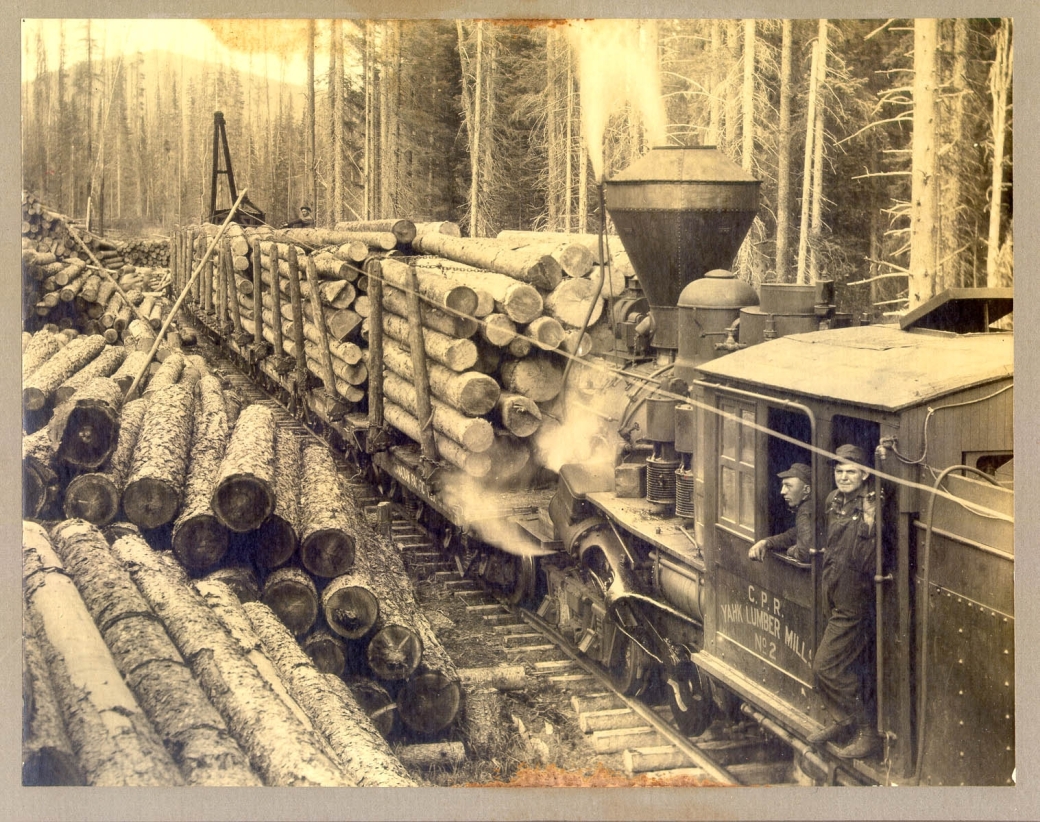

With better concentrating machinery installed in 1908, shipments began to pick up with 584 tons shipped for a value of $20,000. Shipments steadily climbed to 44,000 tons in 1911 with a value of $900,000. Meanwhile, the Hot Air line limped along, with Republic Agent O.E. Fisher, picking up what business he could. He contracted log hauls to sawmills along the line, and organized rail excursions on Sundays to the popular picnic grounds on Curlew Lake The Great Northern’s W&GN, however, with its direct connection to Spokane, took the majority of the the passenger business.

Train No. 256 from Spokane dropped its buffet car at Curlew, and continued on west to Oroville where it terminated. Return train, No. 255, originated there at 6:30 AM, and stopped in Curlew to board passengers bound for Grand Forks or Spokane, and to pick up the buffet car. The 2-1/2 percent grades on the Midway – Oroville portion of the line made it prudent to leave the heavy buffet car at Curlew, since the locomotives assigned to this service were older machines from Dan Corbin’s SF&N with limited pulling capacity. At Karamin, not listed in this timetable, but at Mile 163, passengers and freight were set out for the narrow gauge Belcher Mine Railway which pulled its single passenger car 8 miles up Lambert Creek whenever Conductor Ike Mc Clung had paying traffic.

In the Teens and Twenties of this century, Marcus, Washington was the center of action for all these mining lines. Daily, at noon, the town came to life with sudden energy. No. 259, the morning train from Nelson would arrive at 12:40 with the passengers and express that had come down the Red Mountain Railway to board at Northport. The passengers would hurry into the restaurant, a neatly panted two story building just west of the station, congratulating themselves on being the first to arrive with a choice of tables. No. 259 would be quickly wyed by its crew and set out beside the station on the north leg of the wye to return to Northport and Nelson as No. 260 after lunch. Once parked on the house track, its hungry crew would make their way to the table in the restaurant reserved for GN employees.

At 12:50, No. 255 from Oroville, Curlew and Grand Forks would come rumbling across the great Columbia River bridge to halt on the west leg of wye opposite the restaurant and its passengers would pour off and crowd into the building. At he same time, 12:50, No. 256 was arriving from Spokane and its passengers were on the vestibule steps ready to make a run for the restaurant, shouting their orders as they crowded through the door.

No. 255 was due to depart for Spokane in ten minutes, so its passengers had time only to pick up their box lunches ordered by telegraph from Laurier. At 1:l0, both No 260 for Northport and Nelson, and No. 256 for Grand Forks, Curlew and Oroville were whistling for departure. The diners cursed, shoving last mouthfuls of food into their faces, put down their napkins and hurried out to their trains, suffering the first pangs of heartburn and damning Jim Hill for his belief that twenty minutes was ample time to order and consume a noon meal. The trains, probably a few minutes late, chuffed off, leaving the restaurant employees time to sit down, put their feet up and enjoy a smoke. The whistle blasts from the three trains, resounding from the mountains, died away, the long rumble from the Columbia Bridge was silenced, and the sleepy, riverfront town of Marcus relaxed into a quiet afternoon snooze. It would all happen again at noon the next day.

In Grand Forks, the Hot Air management, defeated by Jim Hill’s competition at Republic, had turned to their North Fork line. They had built 18 miles up the river and then stalled for want of funds at Lynch Creek. An arrangement with the CPR allowed the Canadian Pacific’s trains to use the Hot Air track through town, and its station on 4th Avenue in exchange for Hot Air trackage rights from Westend to Smelter Junction on the CPR line. The North Fork line then ran alongside Smelter Lake, serving a sawmill there, and on up the valley through the settlements at Niagara, Troutdale and Humming Bird where ore from nearby mines was loaded. At two places north of Humming Bird, the wagon road was side by side with the tracks, and to keep the locomotives from frightening horses on the road, a high board fence was erected to separate the track from the road. The road was frequently impassable in bad weather and couples would then resort to pumping a hand car down the Hot Air rails to attend dances at Volcanic Brown’s Camp. The Hot Air was a home town railroad and when locals needed transportation, borrowing a railroad hand car and pumping down the line was customary practice.

The Franklin Camp gold mines, 40 miles to the north were the line’s immediate goal. An ambitious extension was planned to cross Monashee Pass and reach the Okanagan at Vernon, and beyond to the coal mines of the Nicola Valley. However, no one wanted to risk investing in a line Jim Hill had publicly announced he would destroy. A hotel was built at Lynch Creek, the jumping off place for prospectors and miners, and a wagon road to Franklin Camp brought out its ore to be loaded on the Hot Air cars for the Granby smelter.

In 1919, the Trail smelter was interested in getting fluorite from the Rock Candy mine to use as flux. The CPR built the Lynch Creek bridge and extended the Hot Air rails two miles to Archibald where an aerial cable way brought the fluorite to a loading bunker. This, together with log shipments to the sawmill and cedar utility pole shipments, allowed the Hot Air to maintain a weekly service, since the copper mines along the line had shut down with the closing of the Granby smelter.

In the 1930s, the Hecla Mining Company, of Wallace, Idaho, bought the Union mine at Franklin Camp. They built a concentrator and mill, and shipped their concentrates by truck to the Hot Air at Archibald, staving off the line’s abandonment for a few more years. In 1921 the Hot Air’s wooden bridge over the Kettle River between Cuprum and City Station was damaged and there was no money to repair it. That part of the line was abandoned and the CPR trains backed and out of City Station. That accounts for the mileage on the timetable above being figured from Westend, which was the CPR interchange. By 1935 mine traffic on the North Fork line had ceased and the sawmill at Lynch Creek had closed. With no remaining traffic, the CPR pulled the rails. The present steel highway bridge across the North Fork at Bumblebee is the only remaining artifact of the North Fork branch. In September, 1952, the CPR ceased backing its passenger trains into the downtown station and those tracks were pulled. The Great Northern pulled out of Grand Forks on June 15, 1943, closing its station, and pulling its tracks back across the Kettle River to the “Big Y”, three miles south of town where a tiny station was maintained for passengers. Ever since the Hot Air lost most of the contracts for hauling ore from the Eureka Creek mines to the Great Northern, the managers of the Trusts and Guarantee Company back in Ontario had wanted desperately to unload this ailing railroad. In 1906 they sent out James Warren, the former manager of the White Bear mine at Rossland, to either make the Hot Air profitable, or abandon it.

Warren saw at once that the Republic line, in direct competition with Hill’s Great Northern branch, was a loser. It’s only salvation could be as a Canadian Gateway Line for one of the four American transcontinentals in Spokane. Accordingly, the Hot Air had been reorganized in 1905 as the Spokane and British Columbia Railway with lawyer, W.T. Beck, of Republic as president. The line claimed three locomotives, two passenger cars, and sixteen freight cars. These, lettered for the Spokane and B.C.., ran on all Hot Air branches, from Eureka Creek to Lynch Creek. Beck and Warren sent out surveyors to stake out a grade from Republic to Spokane. The location survey ran down the San Poil river to the Hedlund Lumber Company Mill at West Fork which was expected to provide substantial traffic. To encourage investors, a short length of isolated track was laid here, just as had been done on Clark Avenue in Republic in 1902. The survey followed the San Poil south to the Columbia at Keller where the Indiana corporation was planning to build a smelter to process ore from the Keller mines. The Granby company, as well, had issued bonds in 1902 to finance the extension of the Hot Air to the Keller mines so that it could bid for their ores. From Keller, the S&BC was to run along the north bank of the Columbia to the mouth of the Spokane River. A bridge was to cross the Columbia here and the line was to ascend the Spokane River and enter Spokane across the flat prairie north of town. The line was announced with great fanfare in Spokane, and purchases of land were made, not so much for right of way, but as speculations on the development of north Spokane should the S&BC ever build track. A further scheme was announced by which the S&BC would skirt the north edge of town and connect with Dan Corbin’s Spokane International which he had built to bring the Canadian Pacific into Spokane from Yahk, B.C. The idea was to provide a water level coal route from the Crowsnest mines to the Granby and Greenwood smelters, bypassing the CPR’s costly barge route across Kootenay Lake with its “double dockage” charges on every carload of coal, and that costly haul, with double-headed freights, over Mc Rae Pass. Such route, if built, would break Jim Hill’s monopoly on coal to the Granby smelter, something that the CPR dearly wished for. Jim Hill, for his part, sent his surveyors to stake out a parallel line. It was graded, Bluestem to Hawk Creek, and that was a sufficient message to potential investors. The message was received, and the S&BC languished.

Warren and the Hot Air were not alone in these schemes to bring cheaper coal to the Kootenay and Boundary industries. Frederick Blackwell, who had completed his Idaho and Washington Northern Railroad from a Spokane connection to Metalline Falls, a few miles from the Canadian border, maintained a cutoff line from Blanchard to Athol on Corbin’s SIR, so that coal could come over over his line to Trail, B.C. if only the CPR would build a 35 mile connecting line from Trail, up the Pend Orielle River to tie into his rails at Metalline Falls. CPR officials looked at the proposal. It would give them an easy grade to Trail and bypass the awkward Kootenay Lake barge link. But in the end, they rejected the scheme. For the same amount of money required to build up the Pend Orielle, they could put CPR rails around the south end of Kootenay Lake to Nelson, eliminating the barge line and having an All-Canadian line. Having made this decision, they then characteristically omitted to build the Kootenay Lake Line, and barging went on until the 1930s.

Meanwhile, the Milwaukee bought Blackwell’s Idaho and Washington Northern in 1912. Warren and the Hot Air approached the Union Pacific with their Spokane and B. C. Gateway proposal. The UP considered, but in 1917, opted for 50% of Corbin’s SIR and an interchange with the CPR at Yahk. This American timetable gives times and mileage only from the border at Danville. The Belcher mine had closed the previous year, though there are reports that the Mine Railroad still hauled logs for the sawmill at Karamin.

As with the Canadians up the North Fork, the American residents of Danville used the railroad’s hand cars to attend dances in Curlew. Since trains did not run on Sunday, the baseball teams would use the handcars as well to get to games in Republic. With the destruction of the Hot Air’s Grand Forks depot and offices by fire in August, 1908, the early records of the line perished. However, U.S. sources record that from the period March 1, 1909 until June 30, 1915, total revenues of the American segment of the line were $122,956, and expenses $292,461. Possibly, revenues from the North Fork line may have offset this loss to some extent, but it is doubtful that the Hot Air ever operated in the black. Certainly, the Republic line was always a loser. One trip, related by Harry Lembke, illustrates the parlous state of the Hot Air line in its last years. The Lembkes were buying logs from the Trout Creek area and having them brought to Curlew by the Hot Air train. On one trip to pick up logs, the Hot Air locomotive began to lose water through cracked boiler tubes. With the tank empty, they stopped on the Trout Creek Trestle and tried to dip water from the creek with a rope and bucket. But they found the engine was losing water from her boiler as fast as they could pour it in the tank. The crew took the train to the siding just south of the trestle where all piled onto a flat car and coasted all the way back to Danville. (More likely to Curlew, and pumped a hand car from there to Grand Forks.) Another locomotive was fired up at Grand Forks and run down the line to bring back the leaking locomotive and its train.

With the failure to peddle the Spokane and B.C. to an American railroad, J.J. Warren turned to the last remaining asset the Hot Air Line possessed, that charter authorization to build west to the Coast. It was fanciful to believe that the Hot Air, a bankrupt railroad, barely able to run its trains, could be the corporation to accomplish that “Coast to Kootenay” railroad that British Columbians had wanted for so long. But, astonishingly, Warren thought it could. He somehow convinced the CPR that the way to beat Jim Hill’s “Third Main Line” to the Coast, was to lease the Hot Air for its charter, and then finance it to build the long hoped for line. In 1913, the CPR agreed, and leased the Hot Air. Warren and his directors renamed the corporation again (the Canadian part). This time it became “The Kettle Valley Railway,” and with CPR backing, began building west from the Columbia and Western’s dead end at Midway. Under Warren’s direction, and with CPR money, the Hot Air finally succeeded with a hair-raising mountain line through to Hope B.C. and a connection with the Canadian Pacific’s main line to Vancouver.

The Republic line, under its U.S. charter as the Spokane and B.C.., was allowed to declare itself bankrupt in 1920, and ceased operations. It was not worth saving; the CPR in 1921, allowed its assets to be auctioned off and its rails pulled up for salvage. Washington State Highway 21 was built on its grade from Danville to just north of Curlew, and from the present Curlew High School south to Karamin. The Karamin turnoff follows the grade to Trout Creek and the upper part of the Barrett Creek road is on its grade to Swamp Creek.

The Great Northern trackage up Eureka Creek was seeing slight use in the 1930s as the mines were now using a cyanide process to recover the gold and smelting was no longer required. When a sudden flood washed out the north approach to the great looping trestle over Granite Creek trapping a train up Eureka Creek, the railroad decided to pull its tracks back to the Republic station. A temporary fill was put in to rescue the stranded train, and in 1940, the tracks were lifted and an ore loading platform was built near the station to accommodate carload shipments to the Tacoma smelter.

The Day Brothers of San Francisco, bought and consolidated a number of Eureka Creek properties in the 1930s, and kept them in production with modern concentrating machinery and methods. Hecla Mining Company acquired the Day Company’s Eureka Creek properties in 1981 in an unrelated transaction. Hecla engineers, in inspecting the Day properties in Eureka Creek, found them worth working. Hecla worked the mines until 1995 when the Knob Hill mine was finally closed. It had been an extremely long run; 99 years of nearly continuous production from a single mine, extracting 2 million ounces of gold, surpassing Phoenix and Rossland.

Today, (1997) Echo Bay Mining operates several low grade properties on Cooke Mountain, not far from the old Belcher Mine. Santa Fe Pacific Gold Corporation has leased the Golden Eagle claim from Hecla and is drilling on it to assess its value as a possible open pit mine. Republic, the longest lived of the three Boundary Bonanzas, still thrives as a mining town.

Paradoxically, a fragment of the Hot Air Line has outlasted the Canadian Pacific in the Boundary District. When, in 1995, just after completing a tie replacement program on the C&W Midway-Castlegar line, the Canadian Pacific, apparently suffering another panic attack, pulled its tracks back to Castlegar, the industries of Grand Forks were left without a rail connection. The Burlington Northern was still running down its line to Republic, south of town and a surviving piece of Hot Air track still ran from Cuprum to Coopers’ Wye (“Big Y” locally), the BN interchange. To serve the Grand Forks industries, the CPR stationed a diesel switcher at Cuprum and taxied a crew over from Nelson once or twice a week to perform industry switching and interchange cars with the BN. This was wasteful and ridiculous. The crew taxied over from Nelson had to be paid railroad mileage for the trip as union rules required, and the switcher, unprotected from the weather, had to be idled all winter long to keep the coolant from freezing.

Pope and Talbot, operators of the sawmill undertook to form the Grand Forks Railway Company to take over the switching job. Each morning the personnel of the Railroad, Dennis John, Manager, Mario Savaia, Conductor, and Miss Shelley Dahl, Engineer, switch the Grand Forks industries and run the loads down the 1-1/4 miles of Hot Air Track to the BN interchange at Cooper’s Wye. Pope and Talbot provide a shed for winter storage of the switcher. Headquarters is at Cuprum.