The Incredible Journey of Biene’s Engagement Ring

“When you realize you want to spend the rest of your life with somebody, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible.” Nora Ephron

Peter worries about the Future

This chapter contains a highly condensed version of our correspondence. Only parts that seemed relevant to the theme of the initial challenges facing us on either side of the Atlantic are included here. I reorganized some paragraphs only to enhance the flow of the narrative and sometimes added a sentence or two to make for better transitions. What remained is the fascinating account of the incredible journey of Biene’s engagement ring.

May 29th

My dear Peter,

Your latest letter has made me so happy, and all your plans have touched my heart. I would love to write, o Peter, commit such a great ‘foolishness’, landing a job with the IBM Company and let me soon come to you so that through our closeness we can give each other strength to do all the things that you have described to me. But Peter, you are right; we must not be unreasonable. And perhaps time will pass more quickly and more easily than we think. I am so eagerly waiting for the moment, when your letter to my parents will have arrived. I cannot put into words at all how much I miss you. But because I know that you love me I can bear the long wait…

My dear Peter, now that I am going to England to work as an a-pair girl, I have a special wish. I can hardly overcome my fear to ask you for something that I so fervently desire. But I will directly ask you, because you love me. So I really don’t need to be bashful about it. You know, Peter, I would very much like to wear a ring from you, especially now as I am going to England. Not that I couldn’t be as faithful without the ring. You certainly know that, Peter! I wish that everyone could see that I belong to you and that I promised to be faithful to you. You know, Peter, it is a peculiar feeling, but I believe that I would feel like having some kind of protection, because everyone could see that I have you. Can you understand this, Peter? If I didn’t know how much you love me, I would have never found the courage to write you this…

In Love, Your Biene

“May 31st

My dear Biene,

If I had to report on my search for work or my planned studies at the university, I would have nothing to write today. I hope you do not get impatient that the questions about my job and teachers’ training have not been settled yet.

Gradually I am beginning to worry about us and the more I think about the future the more anxious I get. You know, I have a restless heart that is incessantly driving me, even at times troubling and tormenting me, especially when things are not going the way I had planned. This restlessness engenders a yearning for inner peace and security. Dear Biene, you are my alter ego. In you I found everything I did not have. Without you I would be nothing. Because I love you so much, I also want you to be always happy when you are with me. Out of love you are willing to follow me no matter where I live. You emphasized in your last letter that you would even go and cut trees with me if necessary. But did you consider how much you would have to give up not just for a few days, but rather for a lifetime? You would no longer see your dear friends, your classmates, your brother, your father, and your mother. Later I cannot be the substitute for all these dear people. Instead I would like to be your husband and life’s companion. Dear Biene, to put it frankly I fear you will leave far more behind in Germany than what you will gain in Canada. You see, this is how I feel right now. You are on my mind all the time. You walk with me, you talk with me, and I hear warning voices. Perhaps I am totally off base, and one day we will meet again sharing the desire for happiness, security, and contentedness, for which your restless heart is yearning just as much as mine is. However, never would I want that my wish become an obligation on your part. Think it over thoroughly and give me your honest opinion. Please don’t be sad that I have given so much thought to this matter. I am only thinking about what I can do for you to make you happy…

Greetings from the heart, Peter

Biene Withdraws her Wish for an Engagement Ring

Calgary, June 2nd

My dear Biene,

I must quickly write you this letter, and indeed for three reasons. Some very pleasant events have come up during the past two days. First and foremost I must ask you not to take my last letter too seriously. I had no work and I was worrying about our future. I missed you so much, and then I began to ponder about how it would be for you to meet me again poor and penniless. At such moments I worry too much. I believe that you already know that part of me well enough.

Today I came home rather exhausted. Yet I was happy and content. In my mind I saw you receive me tenderly in your arms, perhaps because I looked so very dusty and tired. Now I must let the cat out of the bag. Right on the first day of my search I found work. I have a good, but tough job with a construction company, and I am getting $1.80 an hour. Isn’t that a good beginning? Here I will stay until I find something better.

Yesterday I paid a little visit to the University of Calgary. From the bus stop I walked the last mile up the hill. You would not believe, dear Biene, how the people were gawking, because I was not driving a car. At the registration counter they gave me a very friendly reception. They retained my high school diploma for translation into English. Everything that I needed to know for the teachers’ training program in the Department of Education was in the book that the receptionist handed to me together with the application forms. There you have the latest information from me. I will write you again, whenever I can spare another hour.

Be kissed a thousand times! Your Peter

Velbert, June 4th

…Yes Peter, and then I read your letter. When I came to the line, where your expressed your concerns, a strange mood suddenly took hold of me, as if I was lying with closed eyes on my back bathing in brilliant sunshine. All at once a shudder seized me, because a dark cloud had drifted over the sun and for a moment withdrew all warmth from me. But this really happened only in the twinkling of an eye, because I could not understand why you were writing me this. I thought, ‘Why do you want me to be afraid of the future?’ Now I feel ashamed of these thoughts and I am sad that I even allowed them to surface in my mind. Peter, please, you must forgive me. There are certain days, when I am a little sensitive. So I did not recognize at first why you wrote me about your doubts. It was because you care so much about me and worry about my future happiness. I only saw the words, ‘ Did you consider all this very carefully?’ and ‘I don’t want that my wish become an obligation to you.’ I did not notice all the other words at all, which were so much more important. Fearfully I thought, ‘Doesn’t Peter no longer believe that our love can be much stronger than all the bonds of family and friends put together, and would he resign himself to the fact that I would no longer be willing to come to him any more?’ But immediately I felt sorry that such thoughts occurred to me, and all of a sudden I understood with my whole heart what had motivated you to lay all the possible future problems before my eyes. I am not ignoring them, Peter! I know exactly what it means to leave everything behind one day.

I talked to my mother about it and asked her, if she could bear to see me leave, because you wanted me to become your wife. You will see how great my mother’s love is. I regret more and more that you were unable to come for a visit before you left for Canada. She said it would be quite natural that I would leave her one day. But a mother would only let her children go with a light heart, if she knew that they would be happy…

Dear Peter, I feel just as strongly as you do that I could not be without you! Therefore, you must not ponder and mull over such thoughts any more. They put brakes on your zest for action and initiative. And in the end I would even believe that you cast doubts on our love, and that I could never endure. Peter, please promise me to put these depressing thoughts aside. You know that it is so simple for you to make me happy.

Now I would like to say something regarding my last letter. But I do not want to hurt you, and therefore understand me correctly. I would like to tell you that I am sorry that I had asked you for a ring. Perhaps you are not yet able to fulfill this wish, because you do not have the money or you believe that it isn’t the right time for it yet. Therefore, let us do as if I had never asked for it. I thought it would be nice to wear a ring from you, I also thought that perhaps you would be glad that I would want it. Peter, right from the beginning we two ran a course, which was quite different from the ordinary, and for that reason it is sometimes a bit complicated between us. And yet it could be simple, because I sense from every word from you that in your innermost being you are so closely connected to me. Oh Peter, don’t you understand? You must be able to understand that it is easy to give up something if one loves one another. And never would I like to make you unhappy again as I once did, when I had not yet recognized it.

Greetings with all my heart!

Your Biene

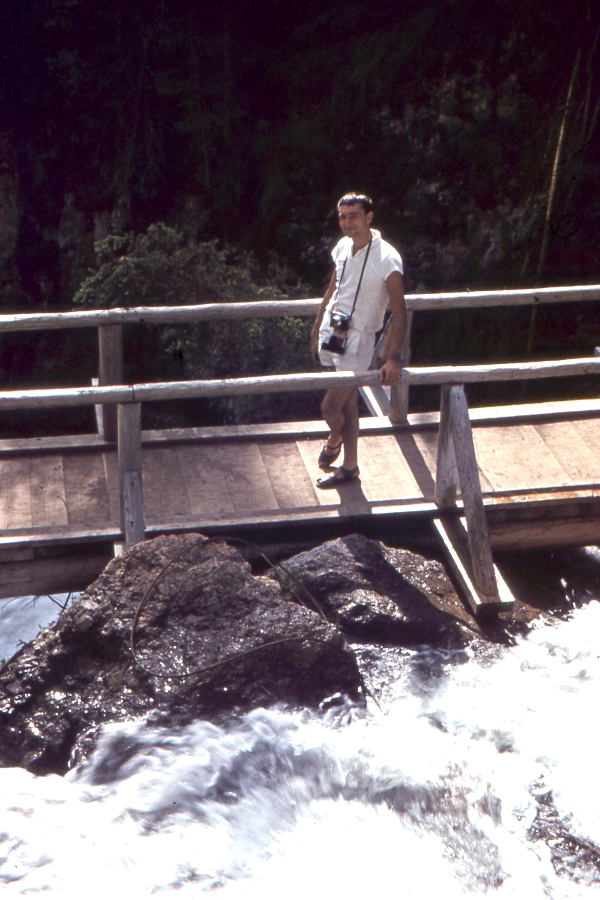

Accident at the Construction Site and a Painful Walk to the Jewelry Store

On Friday, June 18th, I had an accident at the construction site. One of the bricks slipped off the upper board on the scaffold and hit my left knee, which almost immediately swelled up. It could have been much worse. The law did not require safety helmets in the mid 60’s. As I found out much later, I wasn’t even insured and therefore would not have received financial assistance from the Workmen’s Compensation Board. Our boss had deducted the laborers’ insurance and pension contributions from the pay cheques, but kept the money for himself.

Unable to work with so much pain from my swollen knee, I had to call it quits for the day. I promised the foreman that I would report back the following Monday. Instead of returning to my brother’s place, I stepped on the bus, which took me to downtown Calgary. Very close to the bus station stood the building of the Hudson’s Bay department store. With its three stories it was then the highest building in downtown Calgary. From there I limped two and a half blocks on Seventh Avenue to the jewelry store. There on the previous weekend I had ordered Biene’s engagement ring, on account of which so many tender, bitter-sweet feelings had already welled up in our hearts.

I was lucky. Although I had come sooner than planned, the ring was ready. Yet I felt timid and embarrassed in my dirty work clothes and with bloodstains on my pants. I felt oddly out-of-place in this opulent place laid out with red carpets, the walls covered with oak paneling, spotlights illuminating the sparkling wares for the wealthy, with every imaginable piece of expensive jewelry securely placed behind glass cabinets. My heavy German accent was in stark contrast to the polished Oxford English of the gentleman, who was wearing a formal suit. I pulled out four twenty-dollar bills from my back pocket and put the folded bundle on the counter top. It was one week’s worth of hard work. On that very same day Biene’s engagement ring began its odyssey half way around the globe, but never arrived at its intended destination in Germany.

For the longest time I did not know that the letter with its precious content had gone missing, presumably lost in transit somewhere between Calgary and Velbert. Week after week I waited for Biene’s thankful and happy response, while Biene was desperately yearning for a sign of life from me. For her, as we have seen, the ring meant protection, a signal to all that she belonged to me. But perhaps more importantly she perceived it as concrete assurance of my love and faithfulness. Wearing, seeing, touching and feeling it on her finger would have imbued her with a sense of security from within and without. But there was no ring, no letter, not even a card, which would have immediately ended her distress and despair…

Biene Close to Despair

Velbert, June 24th

My dear Peter,

Now I cannot be so long without any mail from you and therefore quickly write me again, and even if there are only a few words! You see, it is the only thing we have of each other. I told you that I would understand if you couldn’t write as often as before. Now I start worrying again and wonder what may have happened to you, if you are doing well or are perhaps sick. Since your last letter it seems like eternity, and I am fervently awaiting a letter from you.

I hope that you received my letters and my card from the Island of Juist. There we spent four carefree and happy days at the North Sea. Every year the Department of English organizes an introductory get-together for the participants in the first semester. More than ever before I had wished you were here to share all these beautiful experiences with me. I met many new friends, but as nice as they all were, nobody can replace you!

The sea, when it is stormy, is so captivating and contributed a great deal to the atmosphere of friendship and harmony in our group, which was of course also the goal of this excursion. One cannot speak any idle words when walking along the beach, struggling against the storm, or viewing the playful waves in motion. If one talks at all, then only words, which come from the heart and reveal a small aspect of one’s inner being. I had to talk about you; for every thought is somewhat connected to you. All my companions wanted to look into the locket with your picture in it. Now they all know you a little, and the boys kept teasing me, ‘How is Canada?’ Whenever I saw one of them coming my way, I already expected a question like that. But I wasn’t cross with them; for they meant it well.

What can I tell you about the sea? You already got to know it certainly much better than I on your voyage to Canada. However, one thing you could not do like I did, that is running into the surf and then being carried by the waves. That was an incredible feeling! We were so relaxed that we sang from morning to evening. Our American exchange student, Pete, who had an almost inexhaustible repertoire of songs, taught us many of them, which we sang with never-ending enthusiasm. It was truly a genuine music festival! Peter, you would have very much liked it too. But I promise you to learn all the songs so that later on we can sing them together. O Peter, if only you had been present! Every time they were singing ‘My Bonnie lies over the ocean, my Bonnie lies over the sea, oh bring back my Bonnie to me!’, I ardently wished the wind just like in the song would carry you to me.

Now I wish from the bottom of my heart that you are doing well. And if something troubles you, dear Peter, please write it to me. I am waiting so longingly for your letter. I even asked after school at the post office, but it was all in vain.

Greetings in love and many hugs, Your Biene

Still no letter from Peter …

Velbert, June 30th

My dear Peter, I don’t know what to do any more! I feel so helpless and powerless, because I don’t know what I should do to get an answer from you. What might have happened that you don’t write to me? It is so terrible having to wait so long, when out of worry my heart is almost breaking. Oh had I only not written that I could understand if you wouldn’t be able to find much time to write. So I don’t know at all, if you don’t write on account of my remark or if there is a more serious cause. But since your last letter so much time passed by that in my inner turmoil and anxiety I turned into a veritable bundle of nerves and I am frightened by the darkest thoughts. Oh Peter, tell me as quickly as possible that all is well! Peter, let me come to you! There must be some work for me there too. I am really not afraid of anything except our separation. I did not want to tell you this, but for the moment I have lost all my courage. How much would I gladly endure, if only I could be with you! Dear Peter, if there is somehow a way, then let us take it. It should not be any more difficult than our long separation. How often did you tell me that we must take our ‘fate’ into our own hands! Surely it will turn out well, if we do it together. I firmly believe this.

Please, dear Peter, quickly write me or else I believe that you are gravely ill. I am constantly praying for you. And if I should have written something in my letters, which hurt your feelings, please forgive me. If I did, it would certainly be, because you are so far away from me and not, because I want to hurt you.

I love you, Peter! Your Biene

Peter finally Breaks his Silence

July 2, Calgary

Dear Biene,

I cannot let you wait any longer. You are like me. You speculate and worry more than it is necessary. Today it was extremely hot again, and yet I had to work for eleven hours. We have to catch up now on the time we lost during the rainy days. But it is not because of my extreme tiredness after work that I did not write to you. The true reason is far more important.

Today, since I know for sure that fate wanted it differently, I can tell you about what happened. Every day I had been waiting for a special message from you. And when you wrote on Monday about your experiences on the Island of Juist and you asked me to write how I was doing, I was already a little concerned, but in spite of your urgent plea I decided to wait for just few more days. But then today on Friday I lost all hope that you actually received my previous letter.

On the German or Canadian side a letter carrier must have stolen it perhaps assuming that it contained something valuable. I am so sad, for he was right. In it I described to you that on the 18th of June, a year and a day after our first date a brick had fallen on my knee and that I was limping to the jeweler’s store. There I picked up the ring I had ordered for you. You can easily imagine the rest of the story. I wanted to give the ring to you, because I was convinced that you truly desired it with all your heart and everything you wrote afterwards was only a renunciation mixed in with painful regret. I saw you in my mind how it first you were perhaps a little angry with me, but then at the end how gratefully and happily you would have acknowledged the receipt of my precious gift. Yes, I am sad that the letter with the ring apparently is lost, but I console myself with the feeling of having turned a good thought immediately into action. Whatever happened on the postal route was beyond my control and we had to accept the bitter fact that the letter was lost.

For more than four weeks Biene and I tried in vain to track down the letter that had gone astray. Obviously it was almost impossible to locate a piece of mail, which I had failed to send by registered letter. After I provided all the particulars, such as type and size of the letter, postage paid and the date, on which I had put the letter in the mailbox, even the thorough and efficient German Post Office was unable to help. Suddenly a ray of hope entered our hearts when I pointed out the possibility that perhaps because of the extra weight and because of insufficient postage the letter had been sent by surface mail, and therefore was still on its way to Germany. This thought occurred to me when I checked the mail I had received from my friend Hans, who had never sent his letters by air. They often took more than a month to arrive. But by the end of July that last glimmer of hope had completely faded. We had indeed resigned ourselves to not seeing the letter with the engagement ring ever again. Besides other things were pressing heavily on our mind. During the long, desperate wait for each other’s reply it became abundantly clear to us and then, when we had resumed our correspondence, even more so that we needed to end our separation much sooner than originally planned. However, shortening the wait time meant that I had to have something concrete, on which to build our romantic aspirations. To find a meaningful job or to enter the teachers’ training program at the university these were the options I was contemplating.

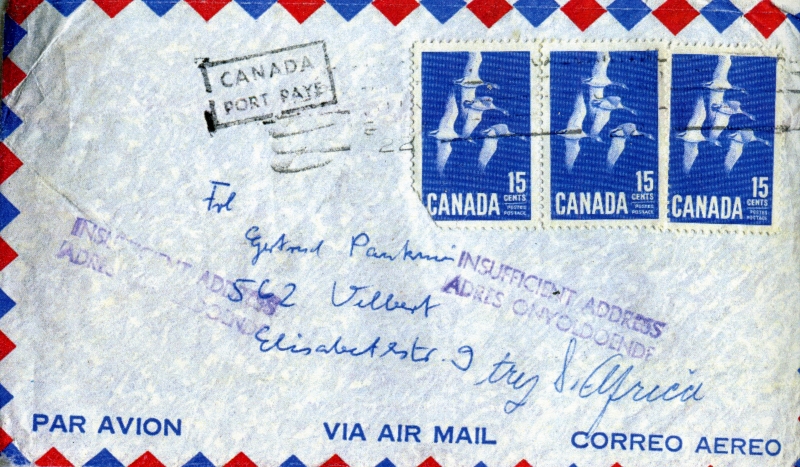

Then a letter arrived that looked strangely familiar. And familiar indeed it was, because it was the missing letter with the ring. In my excitement to fulfill Biene’s wish and dream and perhaps my attention numbed by the pain from my swollen knee, I had forgotten to write Germany on the envelope. Now had Canada Post promptly returned the letter, Biene would not even have noticed the small delay of a day or two. But the overly zealous employee tried to be helpful by second-guessing its destination. To him Velbert sounded Dutch, Elisabethstr. appeared to be British. So our dear postal employee concluded that the country in question had to be South Africa. Thus the letter had traveled half around the globe all the way to Johannesburg by air and had come back ever so slowly by surface mail.

Exactly two months after I had originally mailed this precious letter I put the unopened envelope into a larger one, added a passionately written letter and forwarded it all to Manchester, England, where Biene had already been working as an au-pair girl at the Landes family for a few weeks. But I am getting too far ahead in my story and I must regretfully leave her reaction, her work and her studies for another chapter.